Real-time machine learning: challenges and solutions

[Twitter discussion, LinkedIn]

Updates

- Jan 3, 2023: Update the online features section to differentiate between real-time features and near real-time features.

- If you’re interested in this topic, my book Designing Machine Learning Systems (O’Reilly, June 2022) covers online prediction and continual learning in much more detail.

Real-time machine learning is the approach of using real-time data to generate more accurate predictions and adapt models to changing environments. A year ago, I wrote a post on how machine learning is going real-time. The post must have captured many data scientists’ pain points because, after the post, many companies reached out to me sharing their pain points and discussing how to move their pipelines real time. These conversations prompted me to start a company on real-time machine learning. We have some exciting news I can’t wait to share with you, but that’s a story for another time :-)

In the last year, I’ve talked to ~30 companies in different industries about their challenges with real-time machine learning. I’ve also worked with quite a few to find the solutions. This post outlines the solutions for (1) online prediction and (2) continual learning, with step-by-step use cases, considerations, and technologies required for each level.

Depending on your experience, some stages might seem basic to you. It’s ok to skip those!

Disclaimer: the perspective outlined in this post is heavily influenced by the companies I’ve talked to/worked with, which are predominantly tech companies. Feedback & suggestions are much appreciated.

I’d also love to learn more about the ML workflows at your company for a more accurate perspective. Here’s the link to a 5-minute survey. The results will be aggregated, summarized, and shared with the community. Thank you!

Towards Online Prediction

While I believe that we’re still a few years away from mainstream adoption of continual learning, I’m seeing significant investments from companies to move towards online inference. Starting with a batch prediction system, we’ll discuss what’s needed for a simple online prediction system using batch features, typically useful for in-session adaptation (e.g. giving a user predictions based on their activities within a session on a website or mobile app). Then we’ll continue to discuss how to move to a more mature online prediction system that leverages both complex streaming + batch features.

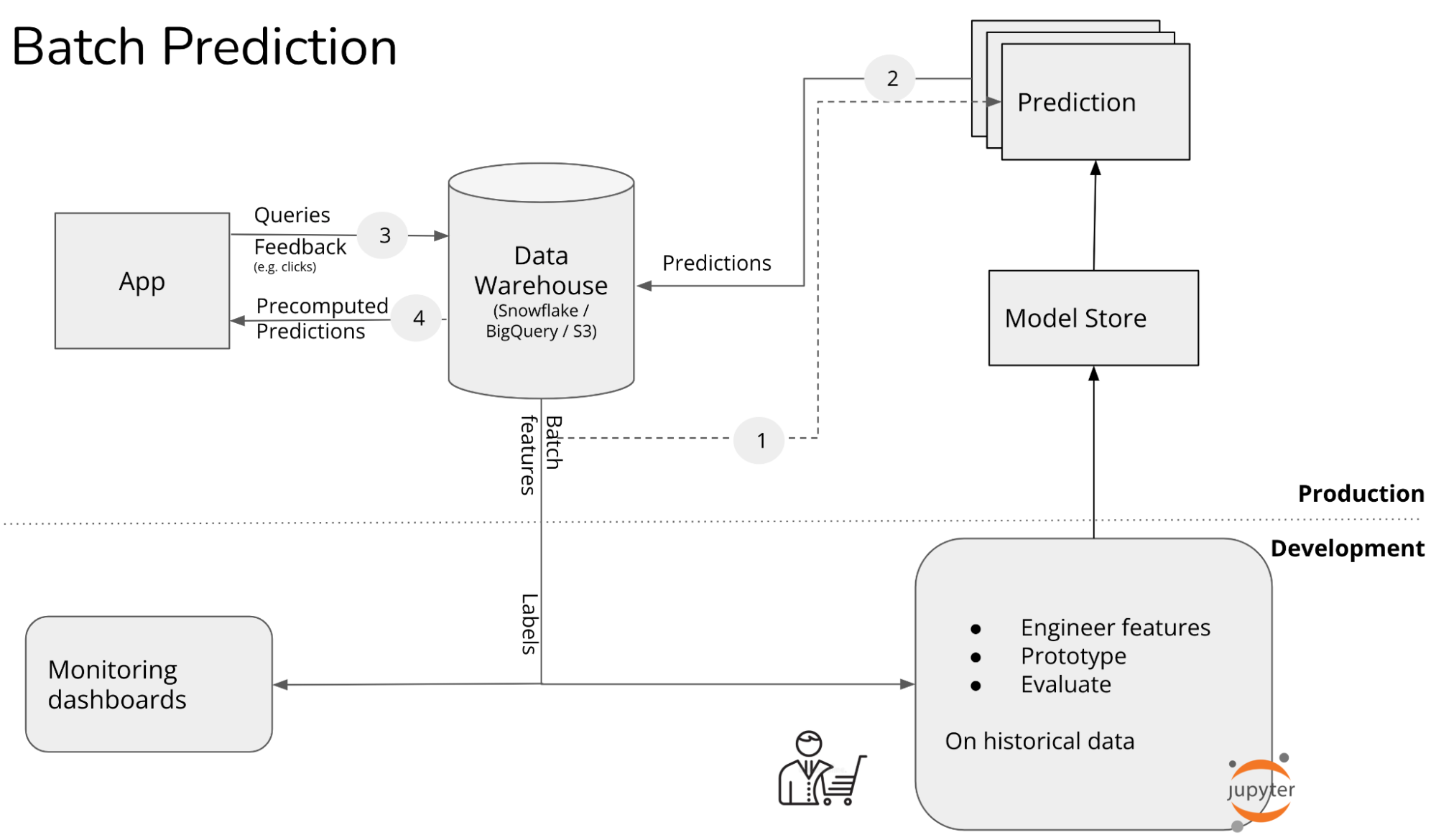

Stage 1. Batch prediction

At this stage, all predictions are precomputed in batch, generated at a certain interval, e.g. every 4 hours or every day. Typical use cases for batch prediction are collaborative filtering, content-based recommendations. Examples of companies that use batch prediction are DoorDash’s restaurant recommendations, Reddit’s subreddit recommendations, Netflix’s recommendations circa 2021. As of this post, Netflix is moving their predictions online.

Batch prediction has many limitations, as outlined in my previous post. Here, I want to quickly go over one example. Consider an e-commerce website where half of their visitors are new users or aren’t logged in. Because these visitors are new, there are no precomputed recommendations personalized to them. By the time the next batch of recommendations is generated, these visitors might have already left without making a purchase because they didn’t find anything relevant to them.

Batch prediction is NOT a prerequisite for online prediction. Batch prediction is largely a product of legacy systems.

In the last decade, big data processing has been dominated by batch systems like MapReduce and Spark, which allow us to periodically process a large amount of data very efficiently. When companies started with machine learning, they leveraged their existing batch systems to make predictions.

If you’re building a new ML system today, it’s possible to start with online prediction.

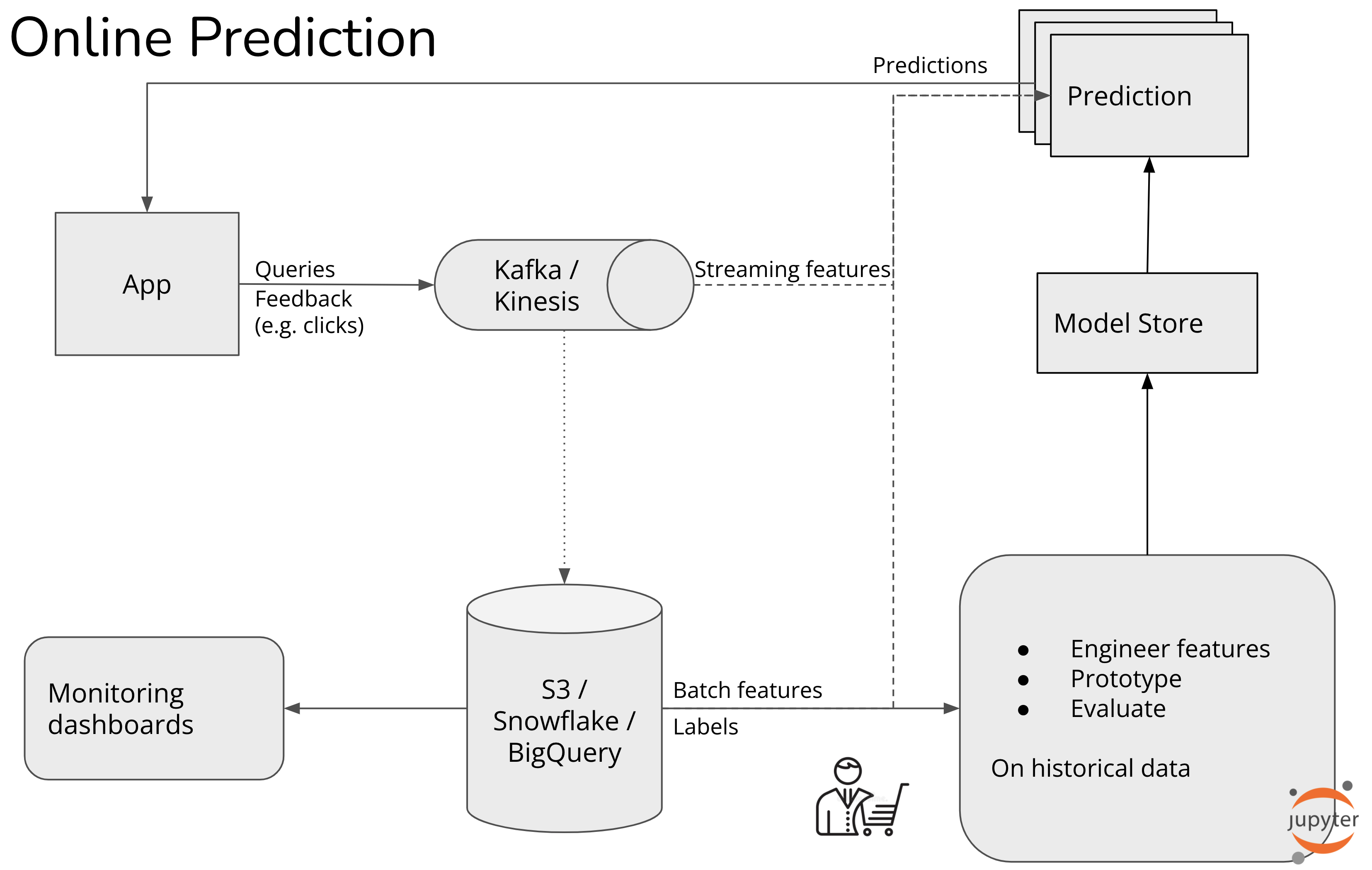

Stage 2. Online prediction with batch features

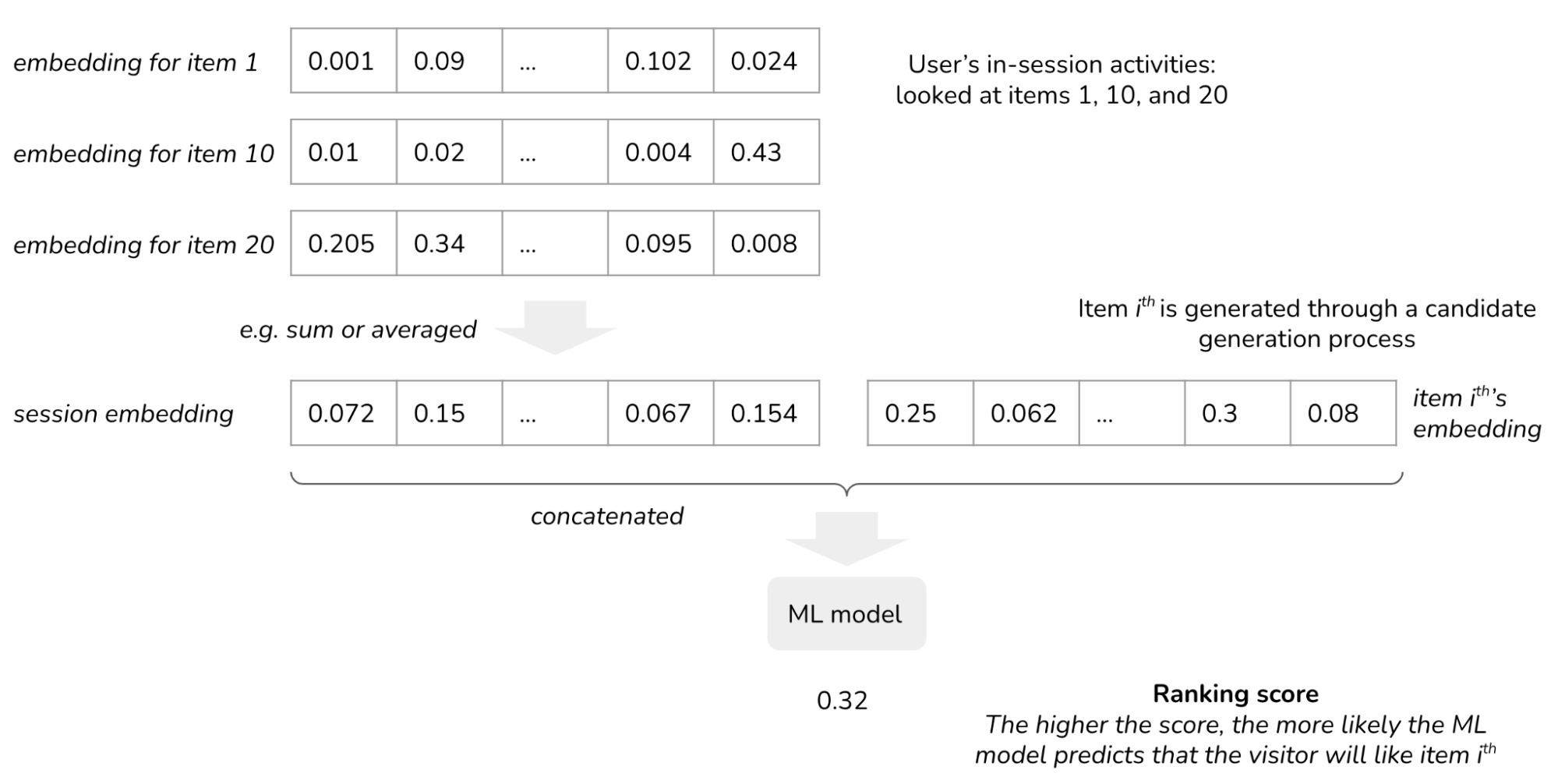

Instead of generating predictions before requests arrive, companies in this stage generate predictions after requests arrive. They collect users’ activities on their apps in real-time. However, these events are only used to look up pre-computed embeddings to generate session embeddings. No features are computed in real-time from streaming data.

Consider the same e-commerce website example in the previous stage. When a new visitor visits your website, instead of suggesting them generic items, you show them items based on their activities. For example, if they have looked at a keyboard and a computer monitor, they’re likely looking at work-from-home setups and your algorithm should recommend relevant items like HDMI cables or monitor mounts.

To do so, you need to collect and process this visitor’s activities as they happen. If this visitor has looked at item 1, item 10, and item 20, you pull out embeddings for items 1, 10, and 20 from your data warehouse. These embeddings are combined (e.g. averaged) to create this visitor’s current session embedding.

You want to find the most relevant items given this session embedding. Naively, you can have a model to rank every item available on your site and show the visitor the items with the highest scores. However, you might have millions of items on your site, and scoring all of them might take too long – you don’t want your visitors to wait forever to see recommendations. Most companies use another algorithm, such as item-item collaborative filtering and k-nearest neighbors, to generate a small number of candidate items (e.g. 1000) to score. This process of generating candidates is called “candidate generation” or “retrieval”. For readers interested, check out Eugene Yan’s primer on session-based recommendations and Google’s free crash course.

The embeddings can be learned separately from or together with the ranking model. If separately, your system will consist of at least three models: one for learning embeddings, one for retrieval, and one for ranking.

Here, we used a recommender system to illustrate this stage, but it can be applied to other tasks including ads CTR, search, or any retrieval task.

The goal of session-based predictions is to increase conversion (e.g. converting first-time visitors to new users, click-through rates) and retention.

The list of companies that are already doing online inference or have online inference on their 2022 roadmaps is growing, including Netflix, YouTube, Roblox, Coveo, etc. Every single company that’s moved to online inference told me that they’re very happy with their metrics wins. I expect that in the next two years, most recommender systems will be session-based: every click, every view, every transaction will be used to generate fresh, relevant recommendations in (near) real-time.

Requirements

For this stage, you will need to:

-

Update your models from batch prediction to session-based predictions.

This means that you might need to add new models. Responsible team: data science/ML.

-

Integrate session data into your prediction service.

Typically, you can do this with streaming infrastructure, which consists of two components:

-

a streaming transport, e.g. Kafka / AWS Kinesis / GCP Dataflow, to move streaming data (users’ activities). Most companies use managed real-time transport – it’s a pain self-host Kafka.

-

a streaming computation engine, e.g. Flink SQL, KSQL, Spark Streaming, to process streaming data. In the case of in-session adaption, this streaming computation engine is responsible for dividing users’ activities into sessions and keeping track of the information within each session (state keeping). Of the three streaming computation engines mentioned here, Flink SQL and KSQL are more recognized in the industry and provide a nice SQL abstraction for data scientists.

Many people believe that online prediction is less efficient, both in terms of cost and performance than batch prediction because processing predictions in batch is more efficient than processing predictions one by one. This is not necessarily true, as discussed in the appendix.

With online prediction, you don’t have to generate predictions for users who aren’t visiting your site. Imagine you run an app where only 2% of your users log in daily – e.g. in 2020, Grubhub had 31 million users and 622,000 daily orders.

If you generate predictions for every user each day, the compute used to generate 98% of your predictions will be wasted.

If your company already uses streaming for logging, this change shouldn’t be too steep. However, this might impose heavier workloads on your streaming infrastructure, which might require upgrading for it to be more efficient/scalable.

Responsible team: data/ML platform.

Side note: A small subset of people I’ve talked to use “streaming prediction” to refer to systems that leverage streaming infrastructure for predictions and “online prediction” to refer to systems that don’t. In this post, “online prediction” encompasses “streaming prediction”.

-

Challenges

The challenges of this stage will be in:

- Inference latency: with batch prediction, you don’t need to worry about the inference latency. With online prediction, however, inference latency is crucial.

- Setting up the streaming infrastructure: Many engineers are still terrified of doing SQL-like joins on streaming even though tooling around it is maturing.

- Having high-quality embeddings, especially if you deal with different item types.

Stage 3. Online prediction with online features

- Batch features are features extracted from historical data, often with batch processing. Also called static features or historical features.

- Online features are features extracted from fresh data. Also called dynamic features.

Depending on how online features are computed, they can be further categorized into one of the two categories: real-time (RT) features and near real-time features.

Real-time features

Real-time features are features computed in real-time, as soon as a prediction request is generated. Say, if you want to compute the number of views your product has had in the last 30 minutes in real-time, here are two of several simple ways you can do so:

- Create a lambda function that takes in all the recent user activities and counts the number of views.

- Store all the user activities in a database like postgres and write a SQL query to retrieve this count.

Because features are computed at prediction time, they are fresh, e.g. in the order of milliseconds.

While real-time features are easy to set up, they’re harder to scale. Because real-time features are computed upon receiving prediction requests, their computation latency adds directly to user-facing latency. Traffic growth and fluctuation can significantly affect computation latency. Complex features might be infeasible to support since they might take too long to compute.

Near RT features

Like batch features, near RT features are also precomputed and at prediction time, the latest values are retrieved and used. Since features are computed async, feature computation latency doesn’t add to user-facing latency. You can use as many features or as complex features as they want.

Unlike batch features, near RT feature values are recomputed much more frequently, so feature staleness can be in the order of seconds (it’s only “near” instead of “completely” real-time.) If a user doesn’t visit your site, its feature values won’t be recomputed, avoiding wasted computation. Near RT features are computed using a streaming processing engine.

If companies at stage 2 require little stream processing, companies at stage 3 might benefit much more from streaming. For example, after a user puts in order on Doordash, they might need the following features to estimate the delivery time:

- Batch features: the mean preparation time of this restaurant in the past

- RT features: how far is the restaurant location from the delivery location

- Streaming features: how many other orders this restaurant currently has, how many dashers will be available in the next 30 minutes

In the case of session-based recommendation discussed in stage 2, instead of just using item embeddings to create session embedding, you might use online features such as how long the user has spent on the site, the number of purchases an item has had in the last 24 hours.

Examples of companies at this stage include Stripe, Uber, Faire for use cases like fraud detection, credit scoring, estimation for driving and delivery, and recommendations.

The number of online features for each prediction can be in the hundreds, if not thousands. Online features can be arbitrarily complex with joins, aggregations over large windows, transformations that depend on other transformations. Architecting a system to compute online features efficiently and affordably is very hard.

Requirements

To move your ML workflow to this stage, you’ll need to:

-

Mature streaming infrastructure with an efficient stream processing engine that can compute all the streaming features with acceptable latency. You need to be able to get a request into your streaming transport and process them quickly enough for the prediction service before the next request arrives.

-

A feature store for managing materialized features and ensuring consistency of stream features during training and prediction. Note: current feature stores often manage materialized streaming features but don’t manage feature computation or the source code for the features.

-

A model store. A stream feature, after being created, needs to be validated. To ensure that a new feature actually helps with your model’s performance, you want to add it to a model, which efficiently creates a new model. Ideally, your model store should help you manage and evaluate models created with new streaming features, but model stores that also evaluate models don’t exist yet. You can potentially delegate part of this to a feature store.

-

Preferably a better development environment. Data scientists currently work off historical data even when they’re creating streaming features, which makes it difficult to come up with and validate new streaming features. What if we can give data scientists direct access to data streams so that they can quickly experiment and validate new stream features? Instead of data scientists only having access to historical data, what if they can also access incoming streams of data from their notebooks?

Discussion: Online prediction for bandits and contextual bandits

Online prediction not only allows your models to make more accurate predictions but also enables bandits for online model evaluation – which is more interesting and more powerful than A/B testing – and as an exploration strategy for generating predictions.

For those unfamiliar, bandit algorithms originated in gambling. A casino has multiple slot machines with different payouts. A slot machine is also known as a one-armed bandit, hence the name. You don’t know which slot machine gives the highest payout. You can experiment over time to find out which slot machine is the best while maximizing your payout.

Multi-armed bandits are algorithms that allow you to balance between exploitation (choosing the slot machine that has paid the most in the past) and exploration (choosing other slot machines that may pay off even more).

Bandits for model evaluation

Currently, the industry’s standard for online model evaluation is A/B testing. With A/B testing, you randomly route traffic to each model for predictions and measure at the end of your trial which model works better.

A/B testing is stateless: you can route traffic to each model without having to know about their current performance. You can do A/B testing even with batch prediction.

When you have multiple models to evaluate, each model can be considered a slot machine whose payout (e.g. prediction accuracy) you don’t know. Bandits allow you to determine how to route traffic to each model for prediction to determine the best model while minimizing wrong predictions shown to your users.

Bandits are stateful: before routing a request to a model, you need to calculate all models’ current performance.

Bandits are well-studied in academia and have been shown to be a lot more data-efficient than A/B testing. In many cases, bandits are even the optimal methods.

Bandits require less data to determine which model is the best, and at the same time, reduce opportunity cost as they route traffic to the better model more quickly.

In this experiment by Google’s Greg Rafferty, A/B test required over 630,000 samples to get a confidence interval of 95%, while a simple bandit algorithm (Thompson Sampling) determined that a model was 5% better than the other with less than 12,000 samples.

See discussions on bandits at LinkedIn, Netflix, Facebook, Dropbox, and Stitch Fix. For a more theoretical view, see chapter 2 of the Reinforcement Learning book (Sutton & Barton, 2020).

Requirements

To do bandits for model evaluation, your system needs the following three requirements.

- Online prediction.

-

Preferably short feedback loops: you need to get feedback on whether a prediction made by a model is good or not to calculate the models’ current performance. The feedback is used to extracted labels for predictions.

Examples of tasks with short feedback loops tasks where labels can be determined from users’ feedback like in recommendations — if users click on a recommendation, the recommendation is inferred to be good. If the feedback loops are short, you can update the performance of each model quickly. If the loops are long, it’s still possible to do bandits, but it’ll take longer to update a model’s performance after it’s made a recommendation.

- A mechanism to collect feedback, calculate and keep track of each model’s performance, as well as route prediction requests to different models based on their current performance.

Because of these requirements, bandits are a lot more difficult to implement than A/B testing. Therefore, not widely used in the industry other than at a few big tech companies.

Contextual bandits as an exploration strategy

If bandits for model evaluation are to determine the payout (e.g. prediction accuracy) of each model, contextual bandits are to determine the payout of each action. In the case of recommendations, an action is an item to show to users, and the payout is how likely a user will click on it.

Disclaimer: some people also call bandits for model evaluation “contextual bandits”. This makes conversations confusing, so in this post, contextual bandits refer to exploration strategies to determine the payout of predictions.

To illustrate this, consider a recommendation system for 10,000 items. Each time, you can recommend 10 items to users. The 10 shown items get users’ feedback on them (click or not click). But you won’t get feedback on the other 9,990 items.

If you keep showing users only the items they most likely click on, you’ll get stuck in a feedback loop, showing only popular items and will never get feedback on less popular items.

Contextual bandits leverage contextual information to balance between showing users the items they will like (exploitation) and showing the items you don’t know much about yet (exploration) while minizing the cost of suboptimal actions.

Contextual bandits are well-researched and have been shown to improve models’ performance significantly (see reports by Twitter, Google). However, contextual bandits are even harder to implement than model bandits, since the exploration strategy depends on the ML model’s architecture (e.g. whether it’s a decision tree or a neural network), which makes it less generalizable across use cases.

Towards Continual Learning

When hearing continual learning, people imagine updating models very frequently, such as every 5 minutes. Many people argue that most companies don’t need updates that frequently because:

- They don’t have traffic for that retraining schedule to make sense.

- Their models don’t decay that fast.

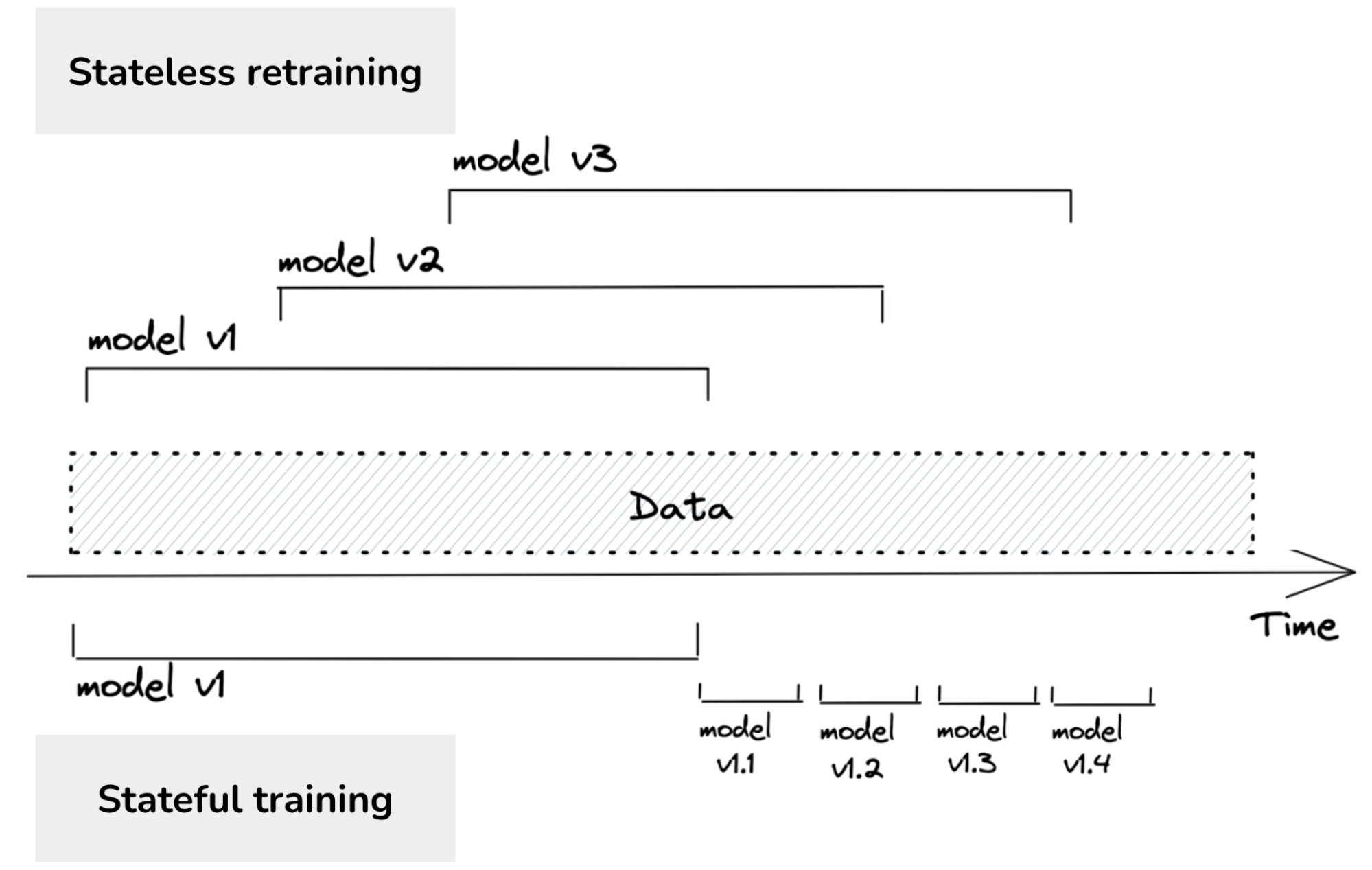

I agree with them. However, continual learning isn’t about the retraining frequency, but the manner in which the model is retrained.

Most companies do stateless retraining – the model is trained from scratch each time. Continual learning means allowing stateful training – the model continues training on new data (fine-tuning).

Once your infrastructure is set up to do stateful training, the training frequency is just a knob to twist. You can update your models once an hour, once a day, or you can update your models whenever your system detects a distribution shift.

There are two types of model updates:

- Model iteration: adding a new feature to an existing model architecture or changing the model architecture.

- Data iteration: same model architecture and features but new data.

As of today, stateful training refers to data iteration. If you change your model architecture or add a new feature, you still have to train the new model from scratch. There has been interesting research showing that it’s possible to do knowledge transfer (Google, 2015) and model surgery (OpenAI, 2019): “transfer trained weights from one network to another after a selection process to determine which sections of the model are unchanged and which must be re-initialized.” Several large research labs have experimented with this, though I’m not aware of any clear results in the industry.

Starting with manual retraining, the first step will be to automate the retraining process. We’ll then move from stateless retraining to stateful training. Last but not least, we’ll discuss continual learning.

Stage 1. Manual, Stateless Retraining

In the beginning, your ML team focuses on developing ML models to solve as many business problems as possible – fraud detection, recommendation, delivery estimation, etc. Because your team is focusing on developing new models, updating existing models takes a backseat. You update an existing model only when:

- the model’s performance has degraded to the point that it’s doing more harm than good, and

- your team has time to update it.

Some of your models are being updated once every six months. Some are being updated once a quarter. Some have been out in the wild for a year and haven’t been updated at all.

The process of updating a model is manual and ad-hoc. Someone, usually on the data platform team, queries data warehouses for new data. Someone else cleans this new data, extracts features from it, retrains that model from scratch on both the old and new data, then exports the updated model into a binary format. Then someone else takes that binary format and deploys the updated model. Oftentimes, the feature/model/processing code was updated during the model retraining, but the changes failed to be replicated to production, causing bugs that are hard to track down.

If this process sounds painfully familiar to you, you’re not alone. A vast majority of companies outside the tech industry – e.g. any company that has adopted ML less than 3 years ago and doesn’t have an ML platform team – are in this stage.

Stage 2. Automated Retraining

Instead of retraining your model manually in an ad-hoc manner, you have a script to automatically execute the retraining process. This is usually done in a batch process, such as Spark.

Most companies with somewhat mature ML infrastructure are in this stage. Some sophisticated companies run experiments to determine the optimal retraining frequency. However, for most companies, the retraining frequency is set based on gut feeling – e.g. “once a day seems about right” or “let’s kick off the retraining process each night when we have idle compute”.

Different models in your pipeline might require different retraining schedules.

In the case of the session-based recommendation above, if your embedding model is separate from your ranking model, then the embedding model might need to be retrained a lot less frequently than the ranking model. For example, you might get away with retraining your embeddings once a week while retraining your ranking models once a day. It’s a different story if you have a lot of new items each day whose embeddings need to be learned.

Things get a lot more complicated if there are dependencies among your models. For example, because the ranking model depends on the embeddings when the embeddings change, the ranking model should be updated too.

Requirements

If your company has ML models in production, it’s likely that your company already has most of the infrastructure pieces needed for automated retraining. The only new piece you’ll need, if you don’t have one already, is a model store to automatically version and store all the code/artifacts needed to reproduce a model.

The simplest model store is probably an S3 bucket that stores serialized blobs of models in some structured manner. If you want a more mature model store, the two solutions that I often hear about are SageMaker (managed service) and MLFlow (open-source). SageMaker is harder to use and doesn’t store your models’ code and artifacts. MLFlow is open-sourced and has more features but if your ML platform has a lot of quirks, it might be hard to get it to work.

You’ll need to write scripts to automate your workflow and configure your infrastructure to automatically sample your data, extract features, and process/annotate labels for retraining. How long this process will take depends on many factors, but here are the two major ones:

- Scheduler. If you already have a CRON scheduler such as Airflow, Argo, wiring the scripts together shouldn’t be that hard.

- Data access and availability. Is all the data you need already collected in your data warehouse? Will you have to join data from multiple organizations? Do you need to build a lot of tables from scratch? Stefan Krawczyk, ML/Data platform manager at Stitch Fix, commented that he suspects most people’s time might be spent here.

Bonus: Log and wait (feature reuse)

When you retrain your model on new data, it’s likely that the new data has already gone through your prediction service, which means features have already been extracted once for predictions. Some companies reuse these extracted features for model updates, which both saves computation and allows for consistency between prediction and training. This approach is known as log and wait. It’s a classic approach to reduce the training-serving skew – bugs caused by mismatches between the production and development environments.

This isn’t yet a popular approach, but it’s getting more popular. I expect that it’ll become a standard soon. Faire has a great blog post discussing the pros and cons of their log and wait approach.

Stage 3. Automated, Stateful Training

Remember that stateful training is when you continue training your model on new data instead of retraining your model from scratch. Stateful retraining allows you to update your model with less data. If you update your model once a month, you might need to retrain your model from scratch on data from the last 3 months. However, if you update your model every day, you only need to fine-tune your model on data from the last day.

Grubhub, after switching from stateless daily retraining to stateful daily retraining, reduced their training cost 45 times (2021).

Another nice property of incremental learning is that you only need to see each data sample at most twice: once during prediction and once during model training. If you’re worried about data privacy, you might be able to discard your data samples after using them.

Requirements

The main thing you need at this stage is a better model store.

- Model lineage: you want to not just version your models but also track their lineage – which model fine-tunes on which model.

- Streaming features reproducibility: you want to be able to time-travel to extract streaming features in the past and recreate the training data for your models at any point in the past in case something happens and you need to debug.

As far as I know, no existing model store has both of these capacities. You might be able to delegate streaming features reproducibility to a feature store, but you’ll likely have to build the solution in-house.

Stage 4. Continual Learning

What I’m working towards and what I hope many companies will eventually adopt is continual learning.

Instead of updating your models based on a fixed schedule, continually update your model whenever data distributions shift and the model’s performance plummets.

The holy grail is when you combine continual learning with edge deployment. Imagine you can ship a base model with a new device – a phone, a watch, a drone, etc. — and the model on that device will continually update and adapt to its environment. There’s no centralized server cost, no need to transfer data back and forth between device and cloud!

Requirements

The switch from stage 3 to stage 4 is steep. You’ll need the following:

-

A mechanism to trigger model updates. This trigger can be time-based (e.g. every 5 minutes), performance-based (e.g. whenever a model performance plummets), or drift-based (e.g. whenever data distributions shift).

Most monitoring solutions today focus on analyzing features – analyzing the summary statistics of a feature (e.g. mean, variance, min, max) and alerting you when significant changes in these statistics happen. However, a model can have hundreds, if not thousands of features. Most feature statistics changes are benign. The problem is not how to detect these changes, but how to know which change actually requires your attention.

- Better ways to continually evaluate your models. Writing a function to update your models isn’t much different from what you’d do in stage 3. The hard part is to ensure that the updated model is working properly. Because you’re updating your models to adapt to changing environments, a stationary test set no longer suffices. You might want to incorporate backtest, progressive evaluation, test in production including shadow deployment, A/B test, canary analysis, and bandits.

- An orchestrator to automatically spin up instances to update and evaluate your models without interrupting the existing prediction service.

Conclusion

Real-time machine learning is largely an infrastructure problem. Solving it will require the data science/ML team and the platform team to work together.

Both online inference and continual learning require a mature streaming infrastructure. The training part of continual learning can be done in batch, but the online evaluation part requires streaming. Many engineers worry that streaming is hard and costly. It was true 3 years ago, but streaming technologies have matured significantly since then. More and more companies are providing solutions to make it easier for companies to move to streaming, including Spark Streaming, Snowflake Streaming, Materialize, Decodable, Vectorize, etc.

To better understand the adoption and challenges of real-time ML in the industry, my team and I are doing a survey. It’d be great if you could share with us your thoughts – it should take around 5 minutes. The results will be aggregated, summarized, and shared with the community. Thank you!

Do get in touch if you want to discuss how I and my team can help you with online prediction, online model evaluation, and automated, stateful training.

Acknowledgments

This post wouldn’t have been possible without the help of a long list of engineers who have been extremely patient with my questions about their workflows.

I’d also like to thank Stefan Krawczyk, Zhenzhong Xu, Max Halford, Goku Mohandas, Alex Egg, Jacopo Tagliabue, and Luke Metz for their thoughtful comments that made this post better.

Thanks Ammar Asmro, Alex Gidiotis, Aditya Soni, Shaosu Liu, Deepanshu Setia, Bonson Sebastian Mampilli, Sean Sheng, and Daniel Tan for your feedback on the survey!

Appendix

On the efficiency of stream processing vs. batch processing

We’ll compare the efficiency along three dimensions: overall cost efficiency, compute performance efficiency, and talent efficiency. Thanks Zhenzhong Xu for this thoughtful analysis!

-

Cost efficiency

Unfortunately, there is no universal cost-efficiency formula between stream and batch processing. It depends on a lot of variables such as latency requirement, data size, late arrival tolerance, failure tolerance, statefulness, etc. Stream processing’s strength is in stateful, continuous, and unbounded data processing. When used properly, often than not it’s less expensive compared to stateless batch processing. An example is if you have to compute a sliding window to score the user engagement during their 30 day trial period, batch processing will have to re-compute 30 days’ worth of data in every single batch, while stateful streaming workload will avoid all the redundant processing, hence less computationally expensive. On the other hand, for one-time processing of extremely large datasets at rest, Batch will still be the top choice. The best teams are the ones who master both.

-

Performance efficiency

Stream Processing is a very sophisticated technology today. Frameworks like Apache Flink are proven to be highly scalable and fully distributed. Stream Processing is optimized for speed and unbounded data. Its performance is measured by throughput per operator, and the availability SLA is often defined as the percentage of events processed within a certain delay tolerance. However, Stream Processing is not optimized for large bounded data processing, and its performance is significantly lower in large historical data processing (e.g., backfill). With that being said, having a cohesive and unified architecture leveraging both streaming and batch’s strength is an active development area. The takeaway here is stream processing and batch all have their strengths and weaknesses. But ultimately as a data processing user, you probably don’t need to worry about the current streaming/batch divide, the gap will close in a couple of years as the abstraction inevitably moves up.

-

Talent efficiency

Today, it’s still a general consensus that streaming is hard to manage in-house. You will need a very strong team of infrastructure engineers who are well versed to do both technical depth and operation work. However, with data processing capabilities becoming more and more commoditized, many companies will start considering buying rather than building in-house. An analogy here, you don’t need nuclear scientists to work for you if what you need is to turn electricity into higher values. (oh well, unless you are running a nuclear powered electricity company :) - in that case, be ready to get the best people you can!)

What do feature stores do?

Thanks Stefan Krawczyk for this analysis.

Feature stores like Tecton and FEAST do some streaming feature computation for you, but they only operate on data that doesn’t need any joins, so it’s unlikely they’ll orchestrate an entire feature computation flow for you.

Sagemaker’s feature store only stores materialized data and requires you to hook it up to pipelines that would do the actual computation. People then reference/use the materialized features in the system, not the actual code that computes them.

If you want to learn any of the above topics, join our Discord chat. We’ll be sharing learning resources and strategies. We might even host learning sessions and discussions if there’s interest. Serious learners only!