Agents

Intelligent agents are considered by many to be the ultimate goal of AI. The classic book by Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (Prentice Hall, 1995), defines the field of AI research as “the study and design of rational agents.”

The unprecedented capabilities of foundation models have opened the door to agentic applications that were previously unimaginable. These new capabilities make it finally possible to develop autonomous, intelligent agents to act as our assistants, coworkers, and coaches. They can help us create a website, gather data, plan a trip, do market research, manage a customer account, automate data entry, prepare us for interviews, interview our candidates, negotiate a deal, etc. The possibilities seem endless, and the potential economic value of these agents is enormous.

This section will start with an overview of agents and then continue with two aspects that determine the capabilities of an agent: tools and planning. Agents, with their new modes of operations, have new modes of failure. This section will end with a discussion on how to evaluate agents to catch these failures.

This post is adapted from the Agents section of AI Engineering (2025) with minor edits to make it a standalone post.

Notes:

- AI-powered agents are an emerging field with no established theoretical frameworks for defining, developing, and evaluating them. This section is a best-effort attempt to build a framework from the existing literature, but it will evolve as the field does. Compared to the rest of the book, this section is more experimental. I received helpful feedback from early reviewers, and I hope to get feedback from readers of this blog post, too.

- Just before this book came out, Anthropic published a blog post on Building effective agents (Dec 2024). I’m glad to see that Anthropic’s blog post and my agent section are conceptually aligned, though with slightly different terminologies. However, Anthropic’s post focuses on isolated patterns, whereas my post covers why and how things work. I also focus more on planning, tool selection, and failure modes.

- The post contains a lot of background information. Feel free to skip ahead if it feels a little too in the weeds!

Agent Overview

The term agent has been used in many different engineering contexts, including but not limited to a software agent, intelligent agent, user agent, conversational agent, and reinforcement learning agent. So, what exactly is an agent?

An agent is anything that can perceive its environment and act upon that environment. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (1995) defines an agent as anything that can be viewed as perceiving its environment through sensors and acting upon that environment through actuators.

This means that an agent is characterized by the environment it operates in and the set of actions it can perform.

The environment an agent can operate in is defined by its use case. If an agent is developed to play a game (e.g., Minecraft, Go, Dota), that game is its environment. If you want an agent to scrape documents from the internet, the environment is the internet. A self-driving car agent’s environment is the road system and its adjacent areas.

The set of actions an AI agent can perform is augmented by the tools it has access to. Many generative AI-powered applications you interact with daily are agents with access to tools, albeit simple ones. ChatGPT is an agent. It can search the web, execute Python code, and generate images. RAG systems are agents—text retrievers, image retrievers, and SQL executors are their tools.

There’s a strong dependency between an agent’s environment and its set of tools. The environment determines what tools an agent can potentially use. For example, if the environment is a chess game, the only possible actions for an agent are the valid chess moves. However, an agent’s tool inventory restricts the environment it can operate in. For example, if a robot’s only action is swimming, it’ll be confined to a water environment.

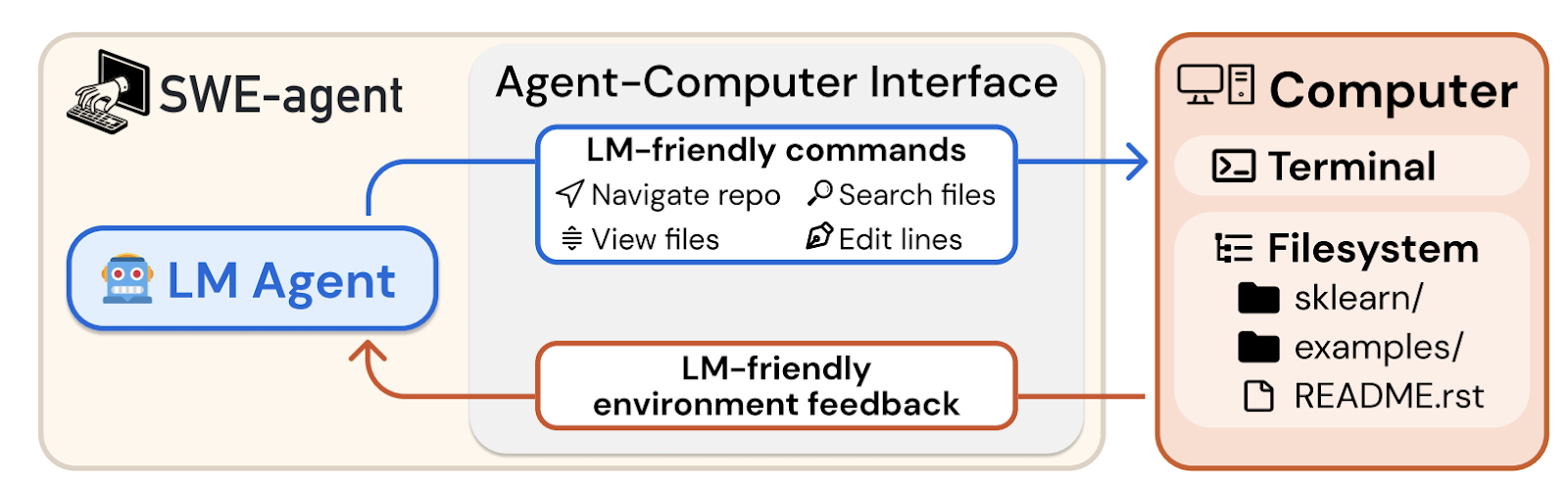

Figure 6-8 shows a visualization of SWE-agent (Yang et al., 2024), an agent built on top of GPT-4. Its environment is the computer with the terminal and the file system. Its set of actions include navigate repo, search files, view files, and edit lines.

An AI agent is meant to accomplish tasks typically provided by the users. In an AI agent, AI is the brain that processes the task, plans a sequence of actions to achieve this task, and determines whether the task has been accomplished.

Let’s return to the RAG system with tabular data in the Kitty Vogue example above. This is a simple agent with three actions:

- response generation,

- SQL query generation, and

- SQL query execution.

Given the query "Project the sales revenue for Fruity Fedora over the next three months", the agent might perform the following sequence of actions:

- Reason about how to accomplish this task. It might decide that to predict future sales, it first needs the sales numbers from the last five years. An agent’s reasoning can be shown as intermediate responses.

- Invoke SQL query generation to generate the query to get sales numbers from the last five years.

- Invoke SQL query execution to execute this query.

- Reason about the tool outputs (outputs from the SQL query execution) and how they help with sales prediction. It might decide that these numbers are insufficient to make a reliable projection, perhaps because of missing values. It then decides that it also needs information about past marketing campaigns.

- Invoke SQL query generation to generate the queries for past marketing campaigns.

- Invoke SQL query execution.

- Reason that this new information is sufficient to help predict future sales. It then generates a projection.

- Reason that the task has been successfully completed.

Compared to non-agent use cases, agents typically require more powerful models for two reasons:

- Compound mistakes: an agent often needs to perform multiple steps to accomplish a task, and the overall accuracy decreases as the number of steps increases. If the model’s accuracy is 95% per step, over 10 steps, the accuracy will drop to 60%, and over 100 steps, the accuracy will be only 0.6%.

- Higher stakes: with access to tools, agents are capable of performing more impactful tasks, but any failure could have more severe consequences.

A task that requires many steps can take time and money to run. A common complaint is that agents are only good for burning through your API credits. However, if agents can be autonomous, they can save human time, making their costs worthwhile.

Given an environment, the success of an agent in an environment depends on the tool it has access to and the strength of its AI planner. Let’s start by looking into different kinds of tools a model can use. We’ll analyze AI’s capability for planning next.

Tools

A system doesn’t need access to external tools to be an agent. However, without external tools, the agent’s capabilities would be limited. By itself, a model can typically perform one action—an LLM can generate text and an image generator can generate images. External tools make an agent vastly more capable.

Tools help an agent to both perceive the environment and act upon it. Actions that allow an agent to perceive the environment are read-only actions, whereas actions that allow an agent to act upon the environment are write actions.

The set of tools an agent has access to is its tool inventory. Since an agent’s tool inventory determines what an agent can do, it’s important to think through what and how many tools to give an agent. More tools give an agent more capabilities. However, the more tools there are, the more challenging it is to understand and utilize them well. Experimentation is necessary to find the right set of tools, as discussed later in the “Tool selection” section.

Depending on the agent’s environment, there are many possible tools. Here are three categories of tools that you might want to consider: knowledge augmentation (i.e., context construction), capability extension, and tools that let your agent act upon its environment.

Knowledge augmentation

I hope that this book, so far, has convinced you of the importance of having the relevant context for a model’s response quality. An important category of tools includes those that help augment the knowledge of your agent. Some of them have already been discussed: text retriever, image retriever, and SQL executor. Other potential tools include internal people search, an inventory API that returns the status of different products, Slack retrieval, an email reader, etc.

Many such tools augment a model with your organization’s private processes and information. However, tools can also give models access to public information, especially from the internet.

Web browsing was among the earliest and most anticipated capabilities to be incorporated into ChatGPT. Web browsing prevents a model from going stale. A model goes stale when the data it was trained on becomes outdated. If the model’s training data was cut off last week, it won’t be able to answer questions that require information from this week unless this information is provided in the context. Without web browsing, a model won’t be able to tell you about the weather, news, upcoming events, stock prices, flight status, etc.

I use web browsing as an umbrella term to cover all tools that access the internet, including web browsers and APIs such as search APIs, news APIs, GitHub APIs, or social media APIs.

While web browsing allows your agent to reference up-to-date information to generate better responses and reduce hallucinations, it can also open up your agent to the cesspools of the internet. Select your Internet APIs with care.

Capability extension

You might also consider tools that address the inherent limitations of AI models. They are easy ways to give your model a performance boost. For example, AI models are notorious for being bad at math. If you ask a model what is 199,999 divided by 292, the model will likely fail. However, this calculation would be trivial if the model had access to a calculator. Instead of trying to train the model to be good at arithmetic, it’s a lot more resource-efficient to just give the model access to a tool.

Other simple tools that can significantly boost a model’s capability include a calendar, timezone converter, unit converter (e.g., from lbs to kg), and translator that can translate to and from the languages that the model isn’t good at.

More complex but powerful tools are code interpreters. Instead of training a model to understand code, you can give it access to a code interpreter to execute a piece of code, return the results, or analyze the code’s failures. This capability lets your agents act as coding assistants, data analysts, and even research assistants that can write code to run experiments and report results. However, automated code execution comes with the risk of code injection attacks, as discussed in Chapter 5 in the section “Defensive Prompt Engineering“. Proper security measurements are crucial to keep you and your users safe.

Tools can turn a text-only or image-only model into a multimodal model. For example, a model that can generate only texts can leverage a text-to-image model as a tool, allowing it to generate both texts and images. Given a text request, the agent’s AI planner decides whether to invoke text generation, image generation, or both. This is how ChatGPT can generate both text and images—it uses DALL-E as its image generator.

Agents can also use a code interpreter to generate charts and graphs, a LaTex compiler to render math equations, or a browser to render web pages from HTML code.

Similarly, a model that can process only text inputs can use an image captioning tool to process images and a transcription tool to process audio. It can use an OCR (optical character recognition) tool to read PDFs.

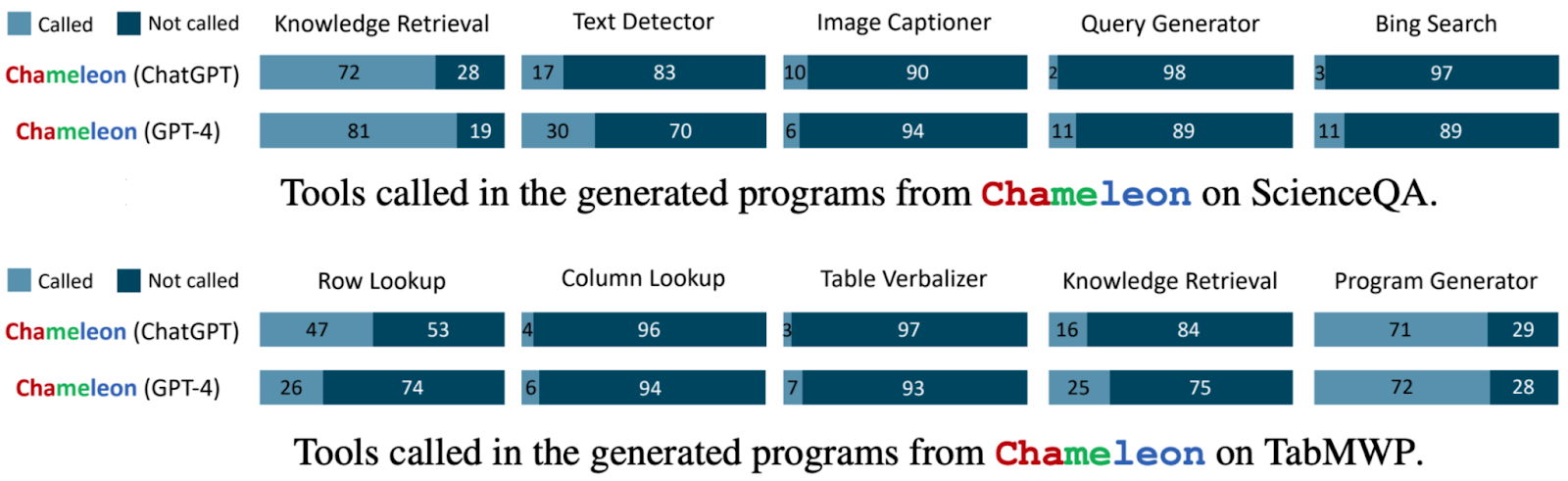

Tool use can significantly boost a model’s performance compared to just prompting or even finetuning. Chameleon (Lu et al., 2023) shows that a GPT-4-powered agent, augmented with a set of 13 tools, can outperform GPT-4 alone on several benchmarks. Examples of tools this agent used are knowledge retrieval, a query generator, an image captioner, a text detector, and Bing search.

On ScienceQA, a science question answering benchmark, Chameleon improves the best published few-shot result by 11.37%. On TabMWP (Tabular Math Word Problems) (Lu et al., 2022), a benchmark involving tabular math questions, Chameleon improves the accuracy by 17%.

Write actions

So far, we’ve discussed read-only actions that allow a model to read from its data sources. But tools can also perform write actions, making changes to the data sources. An SQL executor can retrieve a data table (read) and change or delete the table (write). An email API can read an email but can also respond to it. A banking API can retrieve your current balance, but can also initiate a bank transfer.

Write actions enable a system to do more. They can enable you to automate the whole customer outreach workflow: researching potential customers, finding their contacts, drafting emails, sending first emails, reading responses, following up, extracting orders, updating your databases with new orders, etc.

However, the prospect of giving AI the ability to automatically alter our lives is frightening. Just as you shouldn’t give an intern the authority to delete your production database, you shouldn’t allow an unreliable AI to initiate bank transfers. Trust in the system’s capabilities and its security measures is crucial. You need to ensure that the system is protected from bad actors who might try to manipulate it into performing harmful actions.

Sidebar: Agents and security

Whenever I talk about autonomous AI agents to a group of people, there is often someone who brings up self-driving cars. “What if someone hacks into the car to kidnap you?” While the self-driving car example seems visceral because of its physicality, an AI system can cause harm without a presence in the physical world. It can manipulate the stock market, steal copyrights, violate privacy, reinforce biases, spread misinformation and propaganda, and more, as discussed in the section “Defensive Prompt Engineering” in Chapter 5.

These are all valid concerns, and any organization that wants to leverage AI needs to take safety and security seriously. However, this doesn’t mean that AI systems should never be given the ability to act in the real world. If we can trust a machine to take us into space, I hope that one day, security measures will be sufficient for us to trust autonomous AI systems. Besides, humans can fail, too. Personally, I would trust a self-driving car more than the average stranger to give me a lift.

Just as the right tools can help humans be vastly more productive—can you imagine doing business without Excel or building a skyscraper without cranes?—tools enable models to accomplish many more tasks. Many model providers already support tool use with their models, a feature often called function calling. Going forward, I would expect function calling with a wide set of tools to be common with most models.

Planning

At the heart of a foundation model agent is the model responsible for solving user-provided tasks. A task is defined by its goal and constraints. For example, one task is to schedule a two-week trip from San Francisco to India with a budget of $5,000. The goal is the two-week trip. The constraint is the budget.

Complex tasks require planning. The output of the planning process is a plan, which is a roadmap outlining the steps needed to accomplish a task. Effective planning typically requires the model to understand the task, consider different options to achieve this task, and choose the most promising one.

If you’ve ever been in any planning meeting, you know that planning is hard. As an important computational problem, planning is well studied and would require several volumes to cover. I’ll only be able to cover the surface here.

Planning overview

Given a task, there are many possible ways to solve it, but not all of them will lead to a successful outcome. Among the correct solutions, some are more efficient than others. Consider the query, "How many companies without revenue have raised at least $1 billion?", and the two example solutions:

- Find all companies without revenue, then filter them by the amount raised.

- Find all companies that have raised at least $1 billion, then filter them by revenue.

The second option is more efficient. There are vastly more companies without revenue than companies that have raised $1 billion. Given only these two options, an intelligent agent should choose option 2.

You can couple planning with execution in the same prompt. For example, you give the model a prompt, ask it to think step by step (such as with a chain-of-thought prompt), and then execute those steps all in one prompt. But what if the model comes up with a 1,000-step plan that doesn’t even accomplish the goal? Without oversight, an agent can run those steps for hours, wasting time and money on API calls, before you realize that it’s not going anywhere.

To avoid fruitless execution, planning should be decoupled from execution. You ask the agent to first generate a plan, and only after this plan is validated is it executed. The plan can be validated using heuristics. For example, one simple heuristic is to eliminate plans with invalid actions. If the generated plan requires a Google search and the agent doesn’t have access to Google Search, this plan is invalid. Another simple heuristic might be eliminating all plans with more than X steps.

A plan can also be validated using AI judges. You can ask a model to evaluate whether the plan seems reasonable or how to improve it.

If the generated plan is evaluated to be bad, you can ask the planner to generate another plan. If the generated plan is good, execute it.

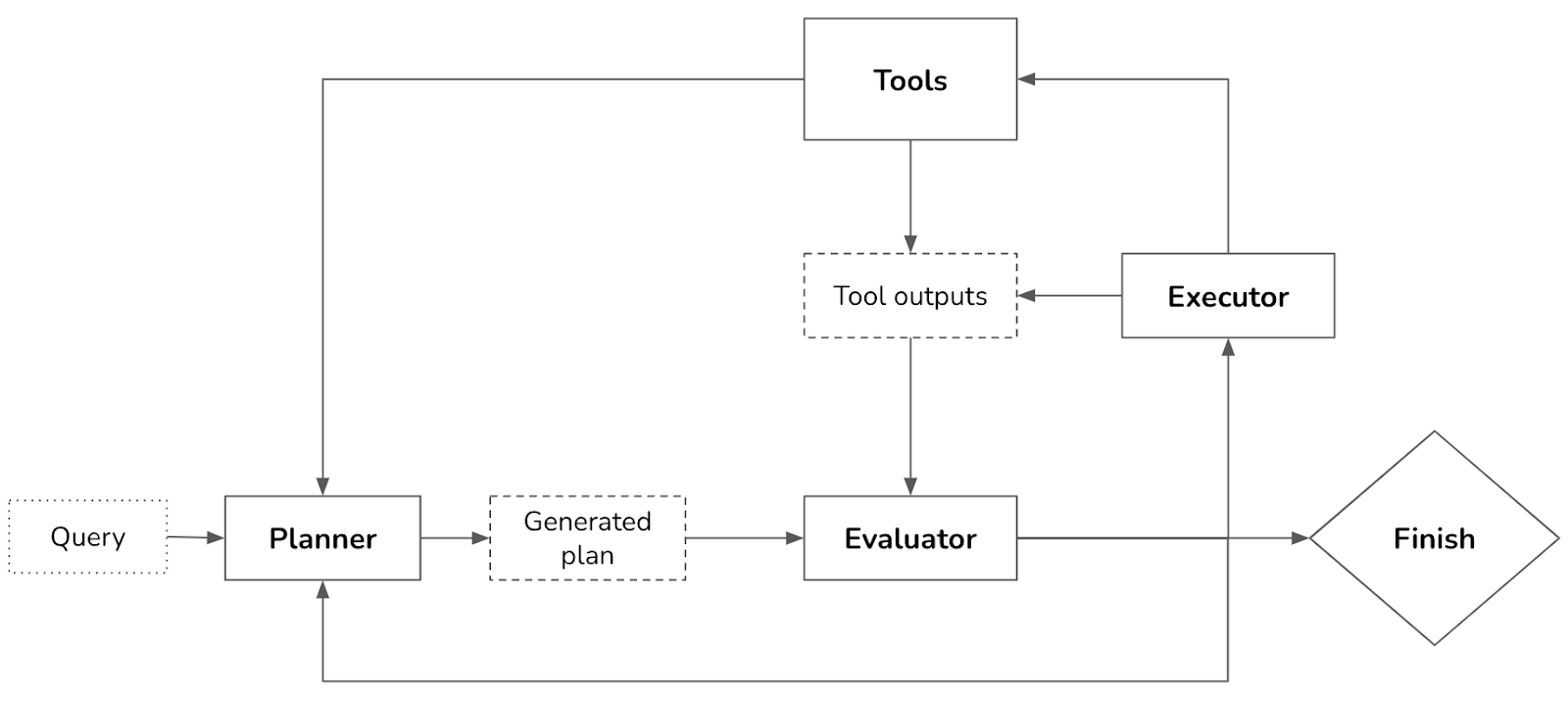

If the plan consists of external tools, function calling will be invoked. Outputs from executing this plan will then again need to be evaluated. Note that the generated plan doesn’t have to be an end-to-end plan for the whole task. It can be a small plan for a subtask. The whole process looks like Figure 6-9.

Your system now has three components: one to generate plans, one to validate plans, and another to execute plans. If you consider each component an agent, this can be considered a multi-agent system. Because most agentic workflows are sufficiently complex to involve multiple components, most agents are multi-agent.

To speed up the process, instead of generating plans sequentially, you can generate several plans in parallel and ask the evaluator to pick the most promising one. This is another latency–cost tradeoff, as generating multiple plans simultaneously will incur extra costs.

Planning requires understanding the intention behind a task: what’s the user trying to do with this query? An intent classifier is often used to help agents plan. As shown in Chapter 5 in the section “Break complex tasks into simpler subtasks“, intent classification can be done using another prompt or a classification model trained for this task. The intent classification mechanism can be considered another agent in your multi-agent system.

Knowing the intent can help the agent pick the right tools. For example, for customer support, if the query is about billing, the agent might need access to a tool to retrieve a user’s recent payments. But if the query is about how to reset a password, the agent might need to access documentation retrieval.

Tip:

Some queries might be out of the scope of the agent. The intent classifier should be able to classify requests as

IRRELEVANTso that the agent can politely reject those instead of wasting FLOPs coming up with impossible solutions.

So far, we’ve assumed that the agent automates all three stages: generating plans, validating plans, and executing plans. In reality, humans can be involved at any stage to aid with the process and mitigate risks.

- A human expert can provide a plan, validate a plan, or execute parts of a plan. For example, for complex tasks for which an agent has trouble generating the whole plan, a human expert can provide a high-level plan that the agent can expand upon.

- If a plan involves risky operations, such as updating a database or merging a code change, the system can ask for explicit human approval before executing or defer to humans to execute these operations. To make this possible, you need to clearly define the level of automation an agent can have for each action.

To summarize, solving a task typically involves the following processes. Note that reflection isn’t mandatory for an agent, but it’ll significantly boost the agent’s performance.

- Plan generation: come up with a plan for accomplishing this task. A plan is a sequence of manageable actions, so this process is also called task decomposition.

- Reflection and error correction: evaluate the generated plan. If it’s a bad plan, generate a new one.

- Execution: take actions outlined in the generated plan. This often involves calling specific functions.

- Reflection and error correction: upon receiving the action outcomes, evaluate these outcomes and determine whether the goal has been accomplished. Identify and correct mistakes. If the goal is not completed, generate a new plan.

You’ve already seen some techniques for plan generation and reflection in this book. When you ask a model to “think step by step”, you’re asking it to decompose a task. When you ask a model to “verify if your answer is correct”, you’re asking it to reflect.

Foundation models as planners

An open question is how well foundation models can plan. Many researchers believe that foundation models, at least those built on top of autoregressive language models, cannot. Meta’s Chief AI Scientist Yann LeCun states unequivocably that autoregressive LLMs can’t plan (2023).

Auto-Regressive LLMs can't plan

— Yann LeCun (@ylecun) September 13, 2023

(and can't really reason).

"While our own limited experiments didn't show any significant improvement [in planning abilities] through fine tuning, it is possible that with even more fine tuning data and effort, the empirical performance may well… https://t.co/rHA5QHi90C

While there is a lot of anecdotal evidence that LLMs are poor planners, it’s unclear whether it’s because we don’t know how to use LLMs the right way or because LLMs, fundamentally, can’t plan.

Planning, at its core, is a search problem. You search among different paths towards the goal, predict the outcome (reward) of each path, and pick the path with the most promising outcome. Often, you might determine that no path exists that can take you to the goal.

Search often requires backtracking. For example, imagine you’re at a step where there are two possible actions: A and B. After taking action A, you enter a state that’s not promising, so you need to backtrack to the previous state to take action B.

Some people argue that an autoregressive model can only generate forward actions. It can’t backtrack to generate alternate actions. Because of this, they conclude that autoregressive models can’t plan. However, this isn’t necessarily true. After executing a path with action A, if the model determines that this path doesn’t make sense, it can revise the path using action B instead, effectively backtracking. The model can also always start over and choose another path.

It’s also possible that LLMs are poor planners because they aren’t given the toolings needed to plan. To plan, it’s necessary to know not only the available actions but also the potential outcome of each action. As a simple example, let’s say you want to walk up a mountain. Your potential actions are turn right, turn left, turn around, or go straight ahead. However, if turning right will cause you to fall off the cliff, you might not consider this action. In technical terms, an action takes you from one state to another, and it’s necessary to know the outcome state to determine whether to take an action.

This means that prompting a model to generate only a sequence of actions like what the popular chain-of-thought prompting technique does isn’t sufficient. The paper “Reasoning with Language Model is Planning with World Model” (Hao et al., 2023) argues that an LLM, by containing so much information about the world, is capable of predicting the outcome of each action. This LLM can incorporate this outcome prediction to generate coherent plans.

Even if AI can’t plan, it can still be a part of a planner. It might be possible to augment an LLM with a search tool and state tracking system to help it plan.

Sidebar: Foundation model (FM) versus reinforcement learning (RL) planners

The agent is a core concept in RL, which is defined in Wikipedia as a field “concerned with how an intelligent agent ought to take actions in a dynamic environment in order to maximize the cumulative reward.”

RL agents and FM agents are similar in many ways. They are both characterized by their environments and possible actions. The main difference is in how their planners work.

- In an RL agent, the planner is trained by an RL algorithm. Training this RL planner can require a lot of time and resources.

- In an FM agent, the model is the planner. This model can be prompted or finetuned to improve its planning capabilities, and generally requires less time and fewer resources.

However, there’s nothing to prevent an FM agent from incorporating RL algorithms to improve its performance. I suspect that in the long run, FM agents and RL agents will merge.

Plan generation

The simplest way to turn a model into a plan generator is with prompt engineering. Imagine that you want to create an agent to help customers learn about products at Kitty Vogue. You give this agent access to three external tools: retrieve products by price, retrieve top products, and retrieve product information. Here’s an example of a prompt for plan generation. This prompt is for illustration purposes only. Production prompts are likely more complex.

SYSTEM PROMPT:

Propose a plan to solve the task. You have access to 5 actions:

* get_today_date()

* fetch_top_products(start_date, end_date, num_products)

* fetch_product_info(product_name)

* generate_query(task_history, tool_output)

* generate_response(query)

The plan must be a sequence of valid actions.

Examples

Task: "Tell me about Fruity Fedora"

Plan: [fetch_product_info, generate_query, generate_response]

Task: "What was the best selling product last week?"

Plan: [fetch_top_products, generate_query, generate_response]

Task: {USER INPUT}

Plan:

There are two things to note about this example:

- The plan format used here—a list of functions whose parameters are inferred by the agent—is just one of many ways to structure the agent control flow.

- The

generate_queryfunction takes in the task’s current history and the most recent tool outputs to generate a query to be fed into the response generator. The tool output at each step is added to the task’s history.

Given the user input “What’s the price of the best-selling product last week”, a generated plan might look like this:

get_time()fetch_top_products()fetch_product_info()generate_query()generate_response()

You might wonder, “What about the parameters needed for each function?” The exact parameters are hard to predict in advance since they are often extracted from the previous tool outputs. If the first step, get_time(), outputs “2030-09-13”, the agent can reason that the parameters for the next step should be called with the following parameters:

fetch_top_products(

start_date="2030-09-07",

end_date="2030-09-13",

num_products=1

)

Often, there’s insufficient information to determine the exact parameter values for a function. For example, if a user asks “What’s the average price of best-selling products?”, the answers to the following questions are unclear:

- How many best-selling products the user wants to look at?

- Does the user want the best-selling products last week, last month, or of all time?

This means that models frequently have to make guesses, and guesses can be wrong.

Because both the action sequence and the associated parameters are generated by AI models, they can be hallucinated. Hallucinations can cause the model to call an invalid function or call a valid function but with wrong parameters. Techniques for improving a model’s performance in general can be used to improve a model’s planning capabilities.

Tips for making an agent better at planning.

- Write a better system prompt with more examples.

- Give better descriptions of the tools and their parameters so that the model understands them better.

- Rewrite the functions themselves to make them simpler, such as refactoring a complex function into two simpler functions.

- Use a stronger model. In general, stronger models are better at planning.

- Finetune a model for plan generation.

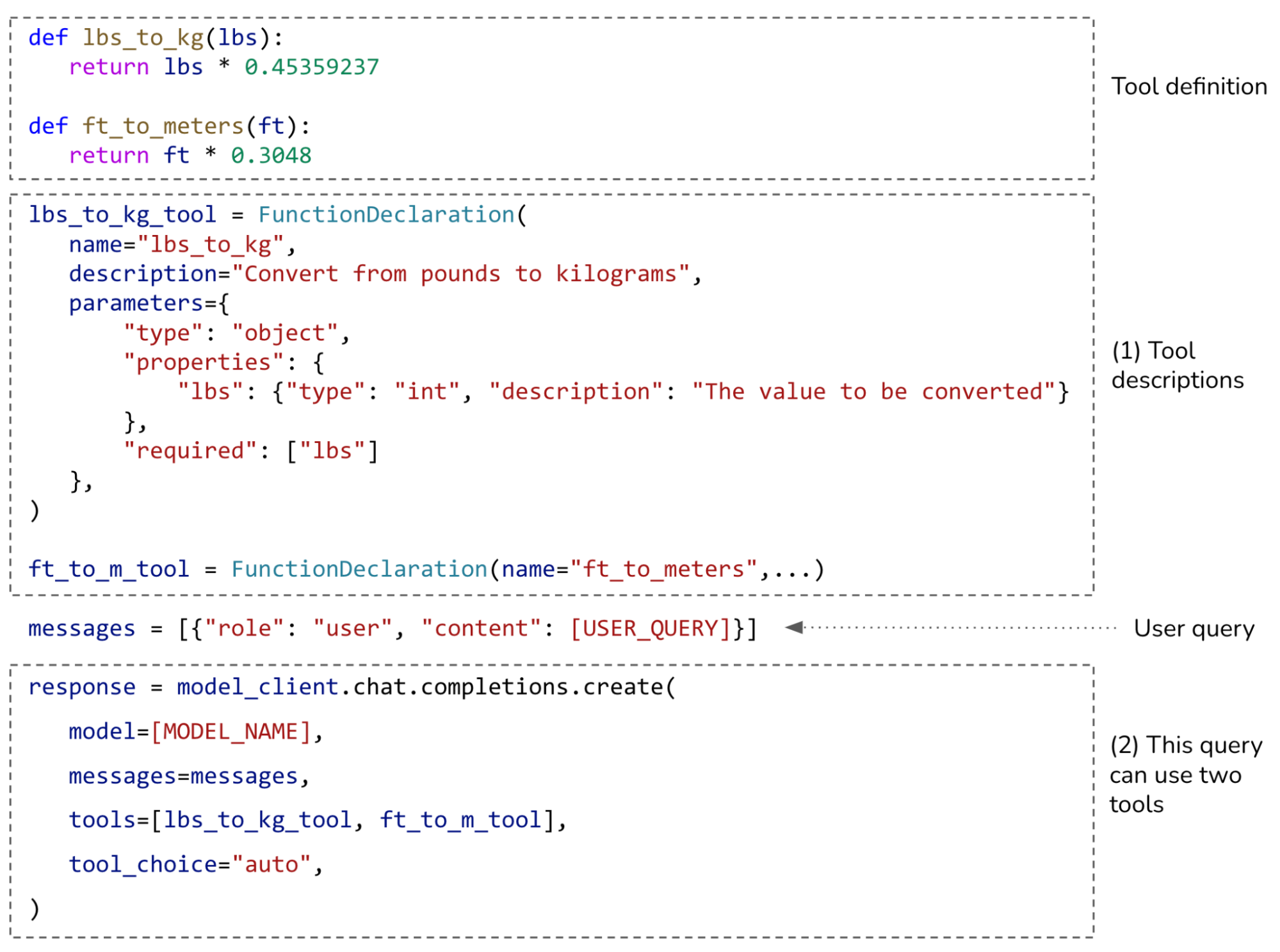

Function calling

Many model providers offer tool use for their models, effectively turning their models into agents. A tool is a function. Invoking a tool is, therefore, often called function calling. Different model APIs work differently, but in general, function calling works as follows:

- Create a tool inventory. Declare all the tools that you might want a model to use. Each tool is described by its execution entry point (e.g., its function name), its parameters, and its documentation (e.g., what the function does and what parameters it needs).

- Specify what tools the agent can use for a query.

Because different queries might need different tools, many APIs let you specify a list of declared tools to be used per query. Some let you control tool use further by the following settings:required: the model must use at least one tool.none: the model shouldn’t use any tool.auto: the model decides which tools to use.

Function calling is illustrated in Figure 6-10. This is written in pseudocode to make it representative of multiple APIs. To use a specific API, please refer to its documentation.

Given a query, an agent defined as in Figure 6-10 will automatically generate what tools to use and their parameters. Some function calling APIs will make sure that only valid functions are generated, though they won’t be able to guarantee the correct parameter values.

For example, given the user query “How many kilograms are 40 pounds?”, the agent might decide that it needs the tool lbs_to_kg_tool with one parameter value of 40. The agent’s response might look like this.

response = ModelResponse(

finish_reason='tool_calls',

message=chat.Message(

content=None,

role='assistant',

tool_calls=[

ToolCall(

function=Function(

arguments='{"lbs":40}',

name='lbs_to_kg'),

type='function')

])

)

From this response, you can evoke the function lbs_to_kg(lbs=40) and use its output to generate a response to the users.

Tip: When working with agents, always ask the system to report what parameter values it uses for each function call. Inspect these values to make sure they are correct.

Planning granularity

A plan is a roadmap outlining the steps needed to accomplish a task. A roadmap can be of different levels of granularity. To plan for a year, a quarter-by-quarter plan is higher-level than a month-by-month plan, which is, in turn, higher-level than a week-to-week plan.

There’s a planning/execution tradeoff. A detailed plan is harder to generate, but easier to execute. A higher-level plan is easier to generate, but harder to execute. An approach to circumvent this tradeoff is to plan hierarchically. First, use a planner to generate a high-level plan, such as a quarter-to-quarter plan. Then, for each quarter, use the same or a different planner to generate a month-to-month plan.

So far, all examples of generated plans use the exact function names, which is very granular. A problem with this approach is that an agent’s tool inventory can change over time. For example, the function to get the current date get_time() can be renamed to get_current_time(). When a tool changes, you’ll need to update your prompt and all your examples. Using the exact function names also makes it harder to reuse a planner across different use cases with different tool APIs.

If you’ve previously finetuned a model to generate plans based on the old tool inventory, you’ll need to finetune the model again on the new tool inventory.

To avoid this problem, plans can also be generated using a more natural language, which is higher-level than domain-specific function names. For example, given the query “What’s the price of the best-selling product last week”, an agent can be instructed to output a plan that looks like this:

get current dateretrieve the best-selling product last weekretrieve product informationgenerate querygenerate response

Using more natural language helps your plan generator become robust to changes in tool APIs. If your model was trained mostly on natural language, it’ll likely be better at understanding and generating plans in natural language and less likely to hallucinate.

The downside of this approach is that you need a translator to translate each natural language action into executable commands. Chameleon (Lu et al., 2023) calls this translator a program generator. However, translating is a much simpler task than planning and can be done by weaker models with a lower risk of hallucination.

Complex plans

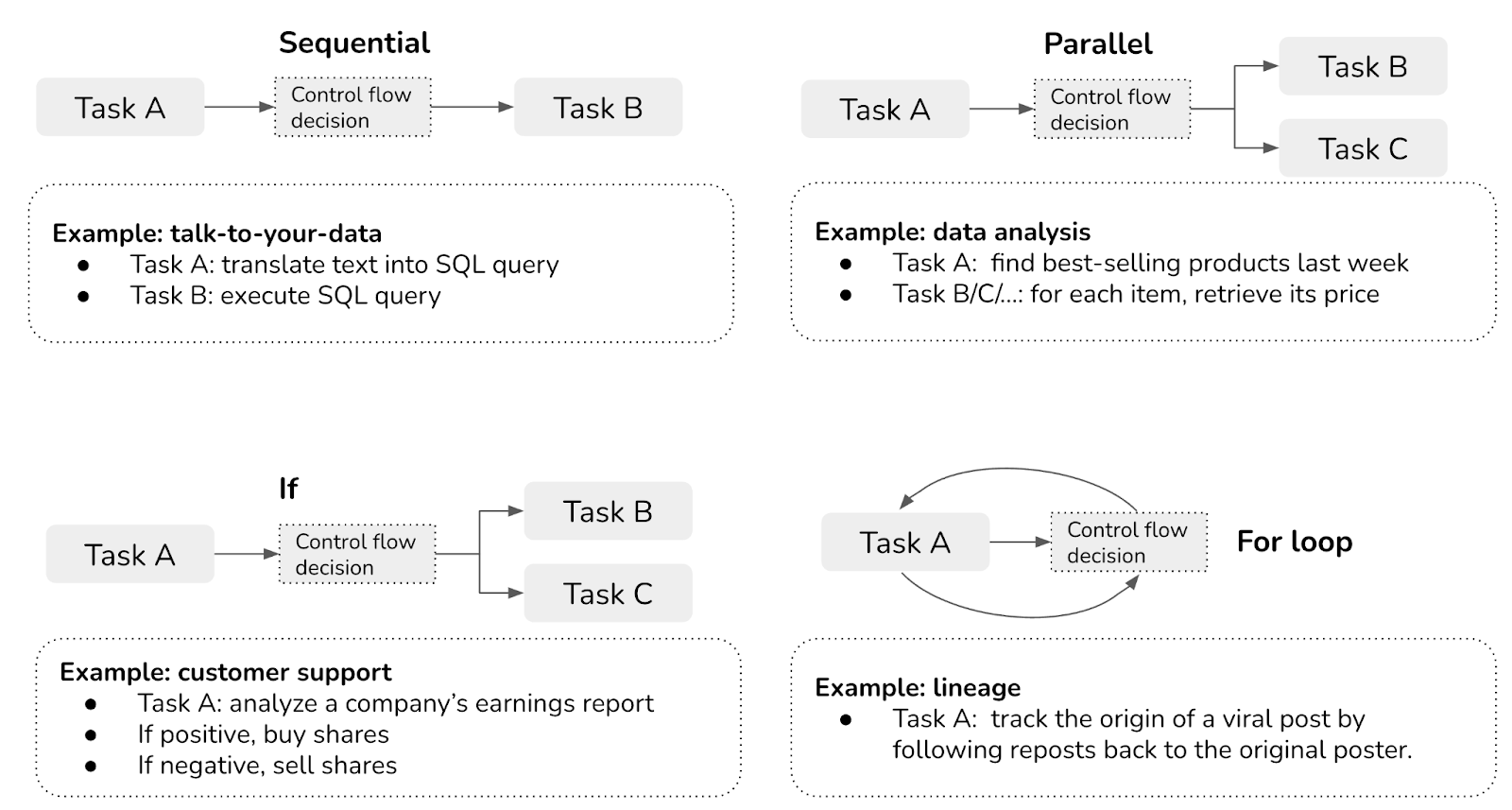

The plan examples so far have been sequential: the next action in the plan is always executed after the previous action is done. The order in which actions can be executed is called a control flow. The sequential form is just one type of control flow. Other types of control flows include the parallel, if statement, and for loop. The list below provides an overview of each control flow, including sequential for comparison:

-

Sequential

Executing task B after task A is complete, possibly because task B depends on task A. For example, the SQL query can only be executed after it’s been translated from the natural language input.

-

Parallel

Executing tasks A and B at the same time. For example, given the query “Find me best-selling products under $100”, an agent might first retrieve the top 100 best-selling products and, for each of these products, retrieve its price.

-

If statement

Executing task B or task C depending on the output from the previous step. For example, the agent first checks NVIDIA’s earnings report. Based on this report, it can then decide to sell or buy NVIDIA stocks. Anthropic’s post calls this pattern “routing”.

-

For loop

Repeat executing task A until a specific condition is met. For example, keep on generating random numbers until a prime number.

These different control flows are visualized in Figure 6-11.

In traditional software engineering, conditions for control flows are exact. With AI-powered agents, AI models determine control flows. Plans with non-sequential control flows are more difficult to both generate and translate into executable commands.

Tip:

When evaluating an agent framework, check what control flows it supports. For example, if the system needs to browse ten websites, can it do so simultaneously? Parallel execution can significantly reduce the latency perceived by users.

Reflection and error correction

Even the best plans need to be constantly evaluated and adjusted to maximize their chance of success. While reflection isn’t strictly necessary for an agent to operate, it’s necessary for an agent to succeed.

There are many places during a task process where reflection can be useful:

- After receiving a user query to evaluate if the request is feasible.

- After the initial plan generation to evaluate whether the plan makes sense.

- After each execution step to evaluate if it’s on the right track.

- After the whole plan has been executed to determine if the task has been accomplished.

Reflection and error correction are two different mechanisms that go hand in hand. Reflection generates insights that help uncover errors to be corrected.

Reflection can be done with the same agent with self-critique prompts. It can also be done with a separate component, such as a specialized scorer: a model that outputs a concrete score for each outcome.

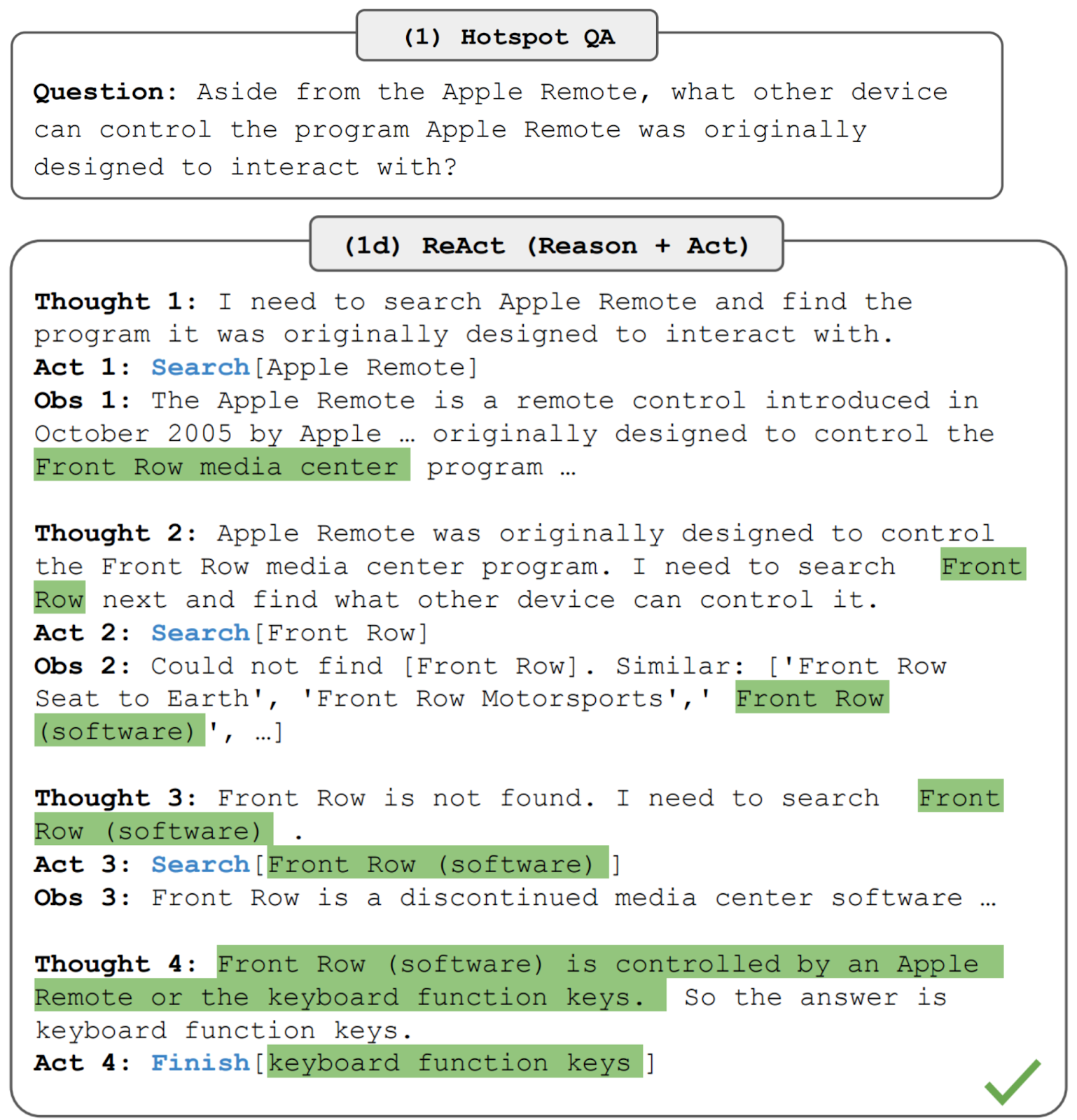

First proposed by ReAct (Yao et al., 2022), interleaving reasoning and action has become a common pattern for agents. Yao et al. used the term “reasoning” to encompass both planning and reflection. At each step, the agent is asked to explain its thinking (planning), take actions, then analyze observations (reflection), until the task is considered finished by the agent. The agent is typically prompted, using examples, to generate outputs in the following format:

Thought 1: …

Act 1: …

Observation 1: …

… [continue until reflection determines that the task is finished] …

Thought N: …

Act N: Finish [Response to query]

Figure 6-12 shows an example of an agent following the ReAct framework responding to a question from HotpotQA (Yang et al., 2018), a benchmark for multi-hop question answering.

You can implement reflection in a multi-agent setting: one agent plans and takes actions and another agent evaluates the outcome after each step or after a number of steps.

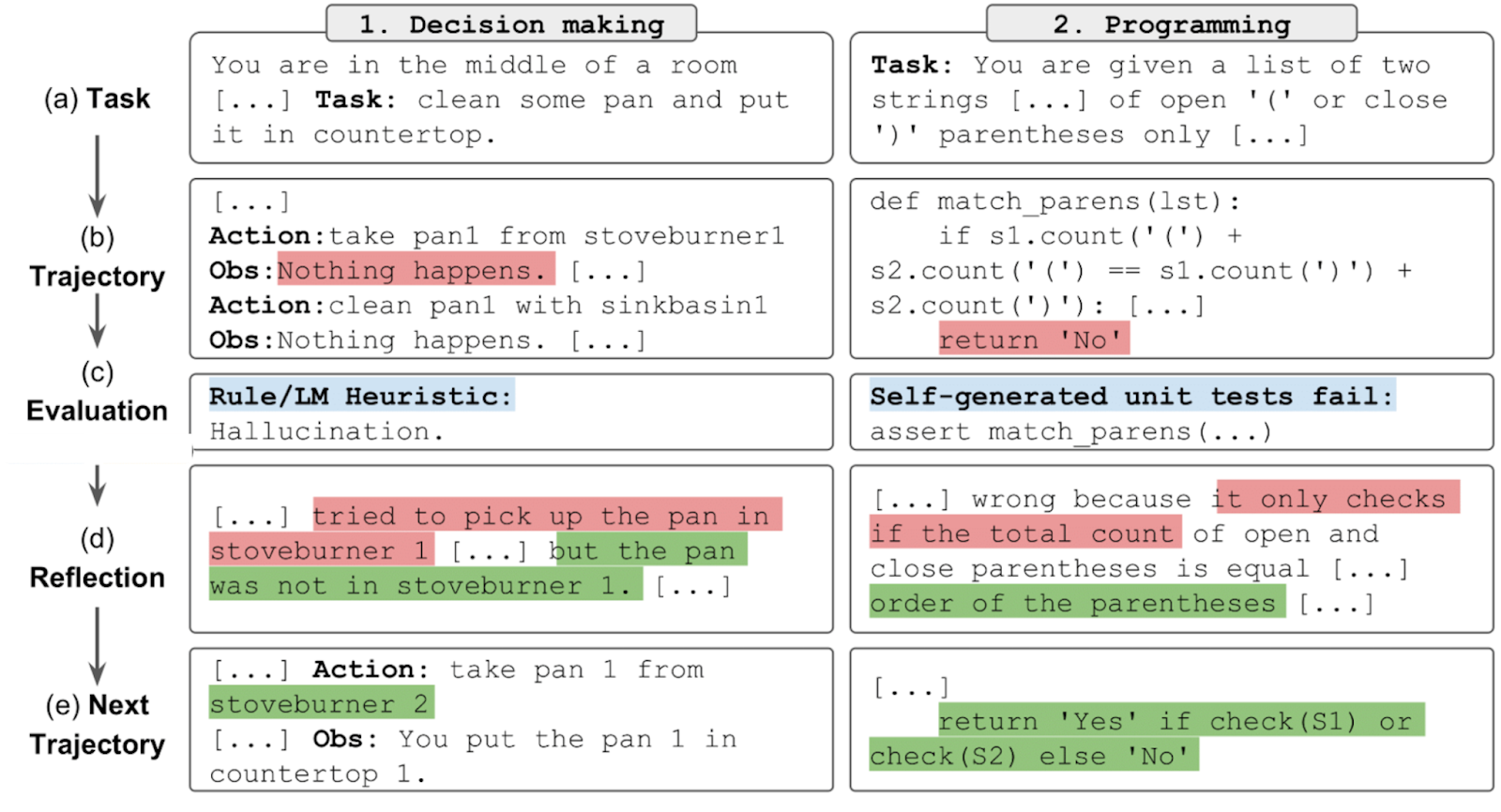

If the agent’s response failed to accomplish the task, you can prompt the agent to reflect on why it failed and how to improve. Based on this suggestion, the agent generates a new plan. This allows agents to learn from their mistakes.

For example, given a coding generation task, an evaluator might evaluate that the generated code fails ⅓ of the test cases. The agent then reflects that it failed because it didn’t take into account arrays where all numbers are negative. The actor then generates new code, taking into account all-negative arrays.

This is the approach that Reflexion (Shinn et al., 2023) took. In this framework, reflection is separated into two modules: an evaluator that evaluates the outcome and a self-reflection module that analyzes what went wrong. Figure 6-13 shows examples of Reflexion agents in action. The authors used the term “trajectory” to refer to a plan. At each step, after evaluation and self-reflection, the agent proposes a new trajectory.

Compared to plan generation, reflection is relatively easy to implement and can bring surprisingly good performance improvement. The downside of this approach is latency and cost. Thoughts, observations, and sometimes actions can take a lot of tokens to generate, which increases cost and user-perceived latency, especially for tasks with many intermediate steps. To nudge their agents to follow the format, both ReAct and Reflexion authors used plenty of examples in their prompts. This increases the cost of computing input tokens and reduces the context space available for other information.

Tool selection

Because tools often play a crucial role in a task’s success, tool selection requires careful consideration. The tools to give your agent depend on the environment and the task, but also depends on the AI model that powers the agent.

There’s no foolproof guide on how to select the best set of tools. Agent literature consists of a wide range of tool inventories. For example:

- Toolformer (Schick et al., 2023) finetuned GPT-J to learn 5 tools.

- Chameleon (Lu et al., 2023) uses 13 tools.

- Gorilla (Patil et al., 2023) attempted to prompt agents to select the right API call among 1,645 APIs.

More tools give the agent more capabilities. However, the more tools there are, the harder it is to efficiently use them. It’s similar to how it’s harder for humans to master a large set of tools. Adding tools also means increasing tool descriptions, which might not fit into a model’s context.

Like many other decisions while building AI applications, tool selection requires experimentation and analysis. Here are a few things you can do to help you decide:

- Compare how an agent performs with different sets of tools.

- Do an ablation study to see how much the agent’s performance drops if a tool is removed from its inventory. If a tool can be removed without a performance drop, remove it.

- Look for tools that the agent frequently makes mistakes on. If a tool proves too hard for the agent to use—for example, extensive prompting and even finetuning can’t get the model to learn to use it—change the tool.

- Plot the distribution of tool calls to see what tools are most used and what tools are least used. Figure 6-14 shows the differences in tool use patterns of GPT-4 and ChatGPT in Chameleon (Lu et al., 2023).

Experiments by Chameleon (Lu et al., 2023) also demonstrate two points:

- Different tasks require different tools. ScienceQA, the science question answering task, relies much more on knowledge retrieval tools than TabMWP, a tabular math problem-solving task.

- Different models have different tool preferences. For example, GPT-4 seems to select a wider set of tools than ChatGPT. ChatGPT seems to favor image captioning, while GPT-4 seems to favor knowledge retrieval.

Tip:

When evaluating an agent framework, evaluate what planners and tools it supports. Different frameworks might focus on different categories of tools. For example, AutoGPT focuses on social media APIs (Reddit, X, and Wikipedia), whereas Composio focuses on enterprise APIs (Google Apps, GitHub, and Slack).

As your needs will likely change over time, evaluate how easy it is to extend your agent to incorporate new tools.

As humans, we become more productive not just by using the tools we’re given, but also by creating progressively more powerful tools from simpler ones. Can AI create new tools from its initial tools?

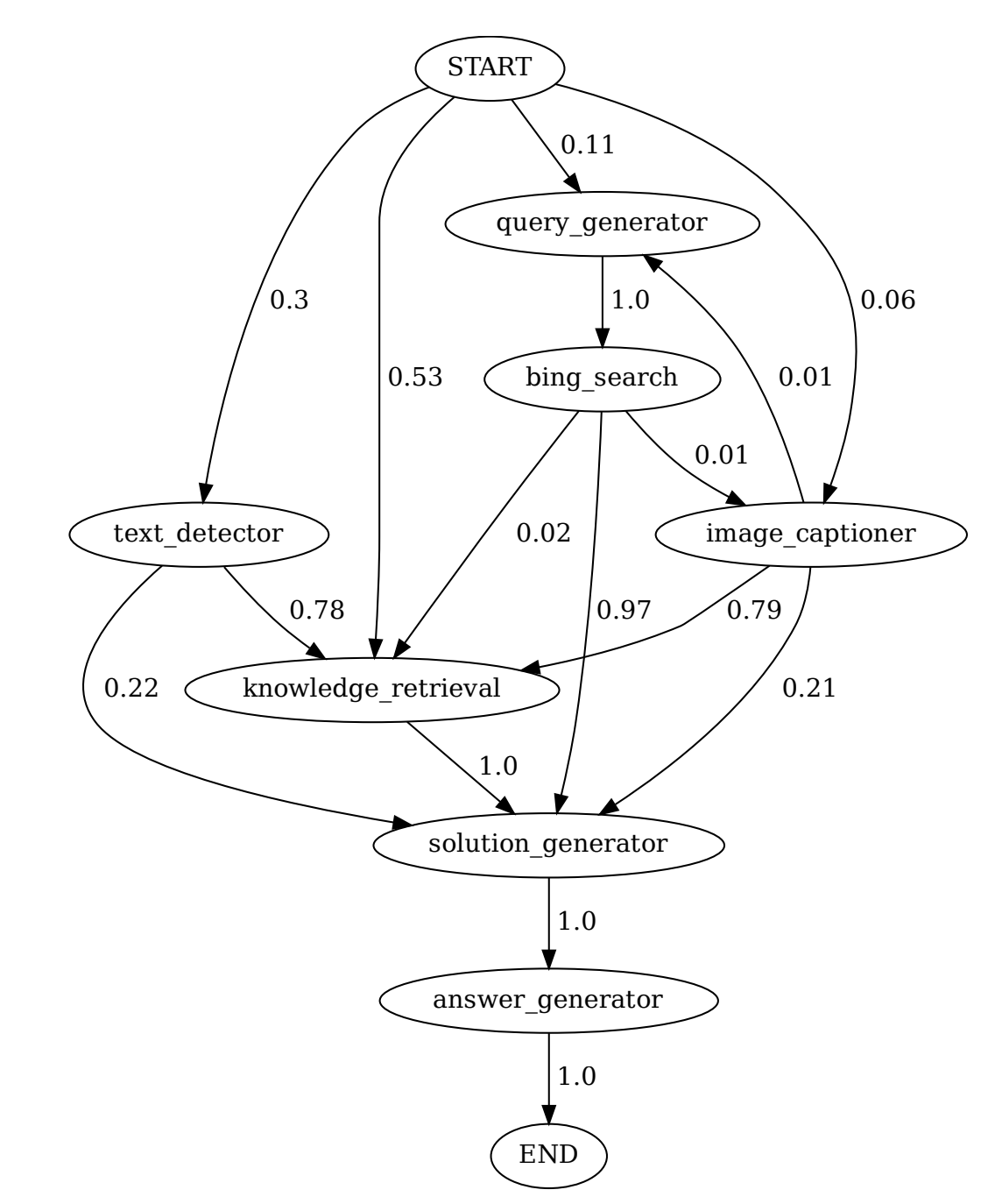

Chameleon (Lu et al., 2023) proposes the study of tool transition: after tool X, how likely is the agent to call tool Y? Figure 6-15 shows an example of tool transition. If two tools are frequently used together, they can be combined into a bigger tool. If an agent is aware of this information, the agent itself can combine initial tools to continually build more complex tools.

Vogager (Wang et al., 2023) proposes a skill manager to keep track of new skills (tools) that an agent acquires for later reuse. Each skill is a coding program. When the skill manager determines a newly created skill is to be useful (e.g., because it’s successfully helped an agent accomplish a task), it adds this skill to the skill library (conceptually similar to the tool inventory). This skill can be retrieved later to use for other tasks.

Earlier in this section, we mentioned that the success of an agent in an environment depends on its tool inventory and its planning capabilities. Failures in either aspect can cause the agent to fail. The next section will discuss different failure modes of an agent and how to evaluate them.

Agent Failure Modes and Evaluation

Evaluation is about detecting failures. The more complex a task an agent performs, the more possible failure points there are. Other than the failure modes common to all AI applications discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, agents also have unique failures caused by planning, tool execution, and efficiency. Some of the failures are easier to catch than others.

To evaluate an agent, identify its failure modes and measure how often each of these failure modes happens.

Planning failures

Planning is hard and can fail in many ways. The most common mode of planning failure is tool use failure. The agent might generate a plan with one or more of these errors.

-

Invalid tool

For example, it generates a plan that contains

bing_search, which isn’t in the tool inventory. -

Valid tool, invalid parameters.

For example, it calls

lbs_to_kgwith two parameters, but this function requires only one parameter,lbs. -

Valid tool, incorrect parameter values

For example, it calls

lbs_to_kg withone parameter,lbs, but uses the value 100 for lbs when it should be 120.

Another mode of planning failure is goal failure: the agent fails to achieve the goal. This can be because the plan doesn’t solve a task, or it solves the task without following the constraints. To illustrate this, imagine you ask the model to plan a two-week trip from San Francisco to India with a budget of $5,000. The agent might plan a trip from San Francisco to Vietnam, or plan you a two-week trip from San Francisco to India that will cost you way over the budget.

A common constraint that is often overlooked by agent evaluation is time. In many cases, the time an agent takes matters less because you can assign a task to an agent and only need to check in when it’s done. However, in many cases, the agent becomes less useful with time. For example, if you ask an agent to prepare a grant proposal and the agent finishes it after the grant deadline, the agent isn’t very helpful.

An interesting mode of planning failure is caused by errors in reflection. The agent is convinced that it’s accomplished a task when it hasn’t. For example, you ask the agent to assign 50 people to 30 hotel rooms. The agent might assign only 40 people and insist that the task has been accomplished.

To evaluate an agent for planning failures, one option is to create a planning dataset where each example is a tuple (task, tool inventory). For each task, use the agent to generate a K number of plans. Compute the following metrics:

- Out of all generated plans, how many are valid?

- For a given task, how many plans does the agent have to generate to get a valid plan?

- Out of all tool calls, how many are valid?

- How often are invalid tools called?

- How often are valid tools called with invalid parameters?

- How often are valid tools called with incorrect parameter values?

Analyze the agent’s outputs for patterns. What types of tasks does the agent fail more on? Do you have a hypothesis why? What tools does the model frequently make mistakes with? Some tools might be harder for an agent to use. You can improve an agent’s ability to use a challenging tool by better prompting, more examples, or finetuning. If all fail, you might consider swapping out this tool for something easier to use.

Tool failures

Tool failures happen when the correct tool is used, but the tool output is wrong. One failure mode is when a tool just gives the wrong outputs. For example, an image captioner returns a wrong description, or an SQL query generator returns a wrong SQL query.

If the agent generates only high-level plans and a translation module is involved in translating from each planned action to executable commands, failures can happen because of translation errors.

Tool failures are tool-dependent. Each tool needs to be tested independently. Always print out each tool call and its output so that you can inspect and evaluate them. If you have a translator, create benchmarks to evaluate it.

Detecting missing tool failures requires an understanding of what tools should be used. If your agent frequently fails on a specific domain, this might be because it lacks tools for this domain. Work with human domain experts and observe what tools they would use.

Efficiency

An agent might generate a valid plan using the right tools to accomplish a task, but it might be inefficient. Here are a few things you might want to track to evaluate an agent’s efficiency:

- How many steps does the agent need, on average, to complete a task?

- How much does the agent cost, on average, to complete a task?

- How long does each action typically take? Are there any actions that are especially time-consuming or expensive?

You can compare these metrics with your baseline, which can be another agent or a human operator. When comparing AI agents to human agents, keep in mind that humans and AI have very different modes of operation, so what’s considered efficient for humans might be inefficient for AI and vice versa. For example, visiting 100 web pages might be inefficient for a human agent who can only visit one page at a time but trivial for an AI agent that can visit all the web pages at once.

Conclusion

At its core, the concept of an agent is fairly simple. An agent is defined by the environment it operates in and the set of tools it has access to. In an AI-powered agent, the AI model is the brain that leverages its tools and feedback from the environment to plan how best to accomplish a task. Access to tools makes a model vastly more capable, so the agentic pattern is inevitable.

While the concept of “agents” sounds novel, they are built upon many concepts that have been used since the early days of LLMs, including self-critique, chain-of-thought, and structured outputs.

This post covered conceptually how agents work and different components of an agent. In a future post, I’ll discuss how to evaluate agent frameworks.

The agentic pattern often deals with information that exceeds a model’s context limit. A memory system that supplements the model’s context in handling information can significantly enhance an agent’s capabilities. Since this post is already long, I’ll explore how a memory system works in a future blog post.