RLHF: Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback

[LinkedIn discussion, Twitter thread]

In literature discussing why ChatGPT is able to capture so much of our imagination, I often come across two narratives:

- Scale: throwing more data and compute at it.

- UX: moving from a prompt interface to a more natural chat interface.

One narrative that is often glossed over is the incredible technical creativity that went into making models like ChatGPT work. One such cool idea is RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback): incorporating reinforcement learning and human feedback into NLP.

RL has been notoriously difficult to work with, and therefore, mostly confined to gaming and simulated environments like Atari or MuJoCo. Just five years ago, both RL and NLP were progressing pretty much orthogonally – different stacks, different techniques, and different experimentation setups. It’s impressive to see it work in a new domain at a massive scale.

So, how exactly does RLHF work? Why does it work? This post will discuss the answers to those questions.

To understand RLHF, we first need to understand the process of training a model like ChatGPT and where RLHF fits in, which is the focus of the first section of this post. The following 3 sections cover the 3 phases of ChatGPT development. For each phase, I’ll discuss the goal for that phase, the intuition for why this phase is needed, and the corresponding mathematical formulation for those who want to see more technical detail.

Currently, RLHF is not yet widely used in the industry except for a few big key players – OpenAI, DeepMind, and Anthropic. However, I’ve seen many work-in-progress efforts using RLHF, so I wouldn’t be surprised to see RLHF used more in the future.

In this post, I assume that readers don’t have specialized knowledge in NLP or RL. If you do, feel free to skip any section that is less relevant for you.

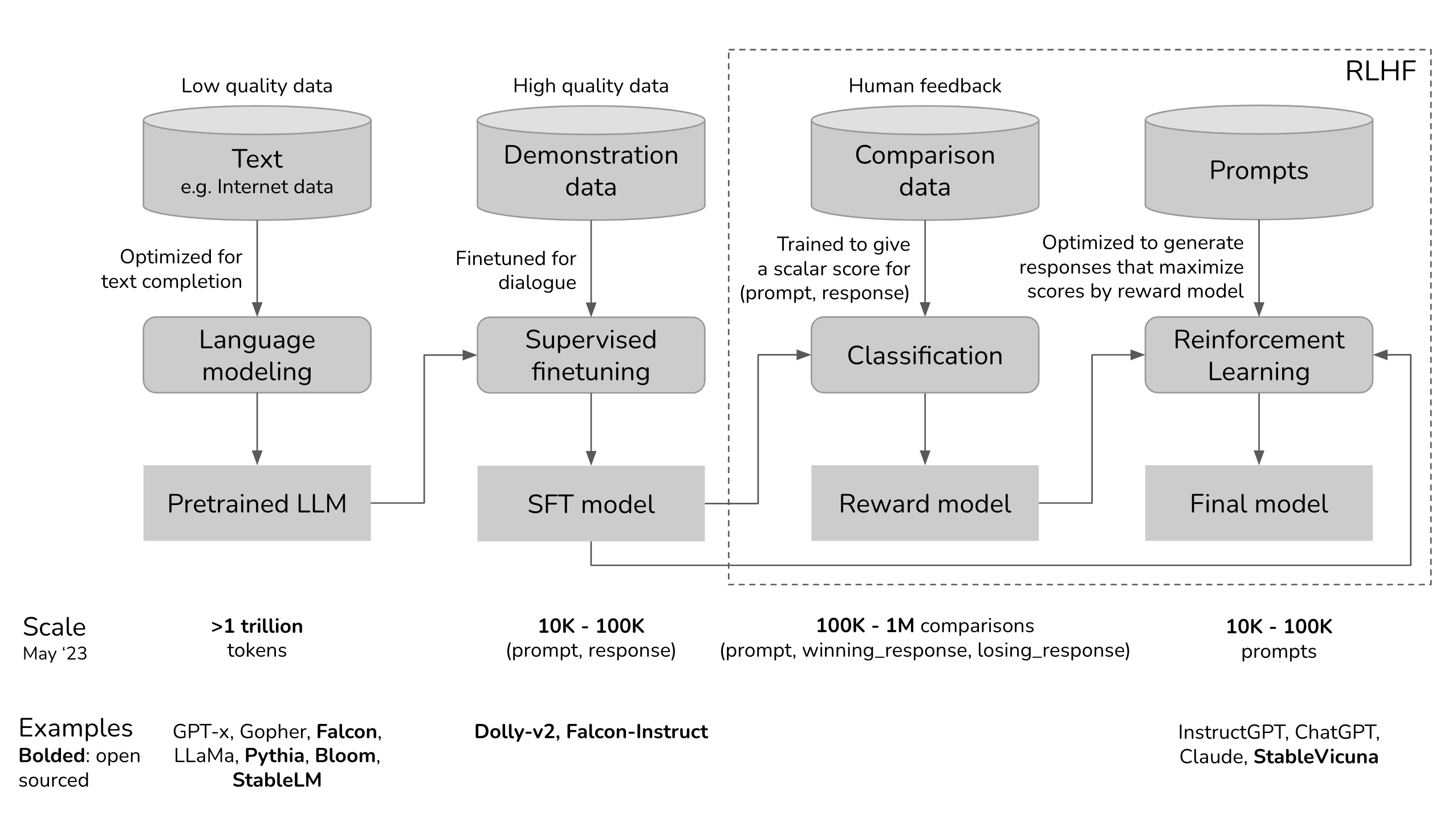

RLHF overview

Let’s visualize the development process for ChatGPT to see where RLHF fits in.

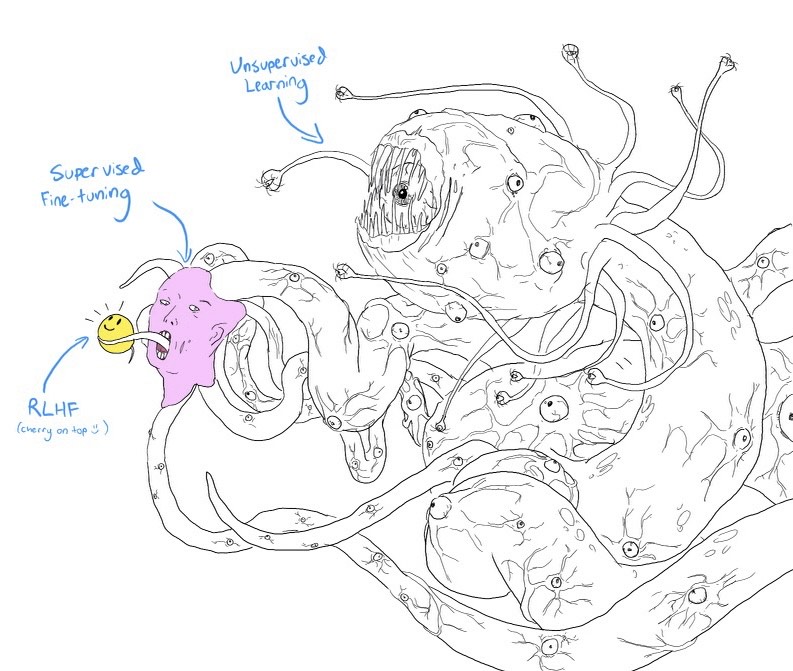

If you squint, this above diagram looks very similar to the meme Shoggoth with a smiley face.

- The pretrained model is an untamed monster because it was trained on indiscriminate data scraped from the Internet: think clickbait, misinformation, propaganda, conspiracy theories, or attacks against certain demographics.

- This monster was then finetuned on higher quality data – think StackOverflow, Quora, or human annotations – which makes it somewhat socially acceptable.

- Then the finetuned model was further polished using RLHF to make it customer-appropriate, e.g. giving it a smiley face.

You can skip any of the three phases. For example, you can do RLHF directly on top of the pretrained model, without going through the SFT phase. However, empirically, combining all these three steps gives the best performance.

Pretraining is the most resource-intensive phase. For the InstructGPT model, pretraining takes up 98% of the overall compute and data resources. You can think of SFT and RLHF as unlocking the capabilities that the pretrained model already has but are hard for users to access via prompting alone.

Teaching machines to learn from human preferences is not new. It’s been around for over a decade. OpenAI started exploring learning from human preference back when their main bet was robotics. The then narrative was that human preference was crucial for AI safety. However, as it turned out, human preference can also make for better products, which attracted a much larger audience.

»»Side note: The abstract from OpenAI’s learning from human preference paper in 2017««

One step towards building safe AI systems is to remove the need for humans to write goal functions, since using a simple proxy for a complex goal, or getting the complex goal a bit wrong, can lead to undesirable and even dangerous behavior. In collaboration with DeepMind’s safety team, we’ve developed an algorithm which can infer what humans want by being told which of two proposed behaviors is better.

Phase 1. Pretraining for completion

The result of the pretraining phase is a large language model (LLM), often known as the pretrained model. Examples include GPT-x (OpenAI), Gopher (DeepMind), LLaMa (Meta), StableLM (Stability AI).

Language model

A language model encodes statistical information about language. For simplicity, statistical information tells us how likely something (e.g. a word, a character) is to appear in a given context. The term token can refer to a word, a character, or a part of a word (like -tion), depending on the language model. You can think of tokens as the vocabulary that a language model uses.

Fluent speakers of a language subconsciously have statistical knowledge of that language. For example, given the context My favorite color is __, if you speak English, you know that the word in the blank is much more likely to be green than car.

Similarly, language models should also be able to fill in that blank. You can think of a language model as a “completion machine”: given a text (prompt), it can generate a response to complete that text. Here’s an example:

- Prompt (from user):

I tried so hard, and got so far - Completion (from language model):

But in the end, it doesn't even matter.

As simple as it sounds, completion turned out to be incredibly powerful, as many tasks can be framed as completion tasks: translation, summarization, writing code, doing math, etc. For example, give the prompt: How are you in French is ..., a language model might be able to complete it with: Comment ça va, effectively translating from one language to another.

To train a language model for completion, you feed it a lot of text so that it can distill statistical information from it. The text given to the model to learn from is called training data. Consider a language that contains only two tokens 0 and 1. If you feed a language model the following sequences as training data, the language model might distill that:

- If the context is

01, the next tokens are likely01 - If the context is

0011, the next tokens are likely0011

0101

010101

01010101

0011

00110011

001100110011

Since language models mimic its training data, language models are only as good as their training data, hence the phrase “Garbage in, garbage out”. If you train a language model on Reddit comments, you might not want to take it home to show to your parents.

Mathematical formulation

- ML task: language modeling

- Training data: low-quality data

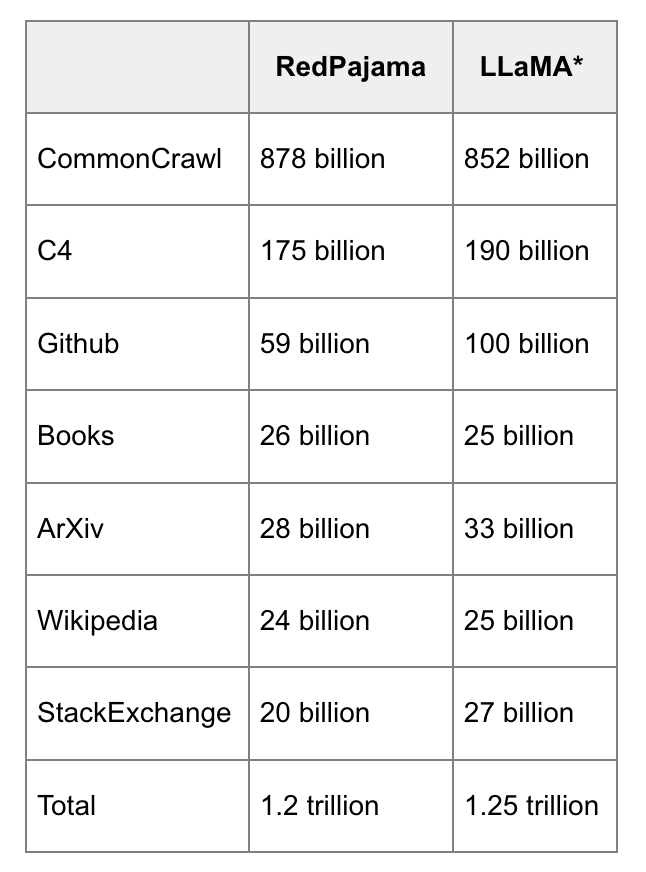

- Data scale: usually in the order of trillions of tokens as of May 2023.

- GPT-3’s dataset (OpenAI): 0.5 trillion tokens. I can’t find any public info for GPT-4, but I’d estimate it to use an order of magnitude more data than GPT-3.

- Gopher’s dataset (DeepMind): 1 trillion tokens

- RedPajama (Together): 1.2 trillion tokens

- LLaMa’s dataset (Meta): 1.4 trillion tokens

- Model resulting from this process: LLM

- \(LLM_\phi\): the language model being trained, parameterized by \(\phi\). The goal is to find \(\phi\) for which the cross entropy loss is minimized.

- \([T_1, T_2, ..., T_V]\): vocabulary – the set of all unique tokens in the training data.

- \(V\): the vocabulary size.

- \(f(x)\): function mapping a token to its position in the vocab. If \(x\) is \(T_k\) in the vocab, \(f(x) = k\).

- Given the sequence \((x_1, x_2, ..., x_n)\), we’ll have \(n\) training samples:

- Input: \(x =(x_1, x_2, ..., x_{i-1})\)

- Ground truth: \(x_i\)

- For each training sample \((x, x_i)\):

- Let \(k = f(x_i)\)

- Model’s output: \(LLM(x)= [\bar{y}_1, \bar{y}_2, ..., \bar{y}_V]\). Note: \(\sum_j\bar{y}_j = 1\)

- The loss value: \(CE(x, x_i; \phi) = -\log\bar{y}_k\)

- Goal: find \(\phi\) to minimize the expected loss on all training samples. \(CE(\phi) = -E_x\log\bar{y}_k\)

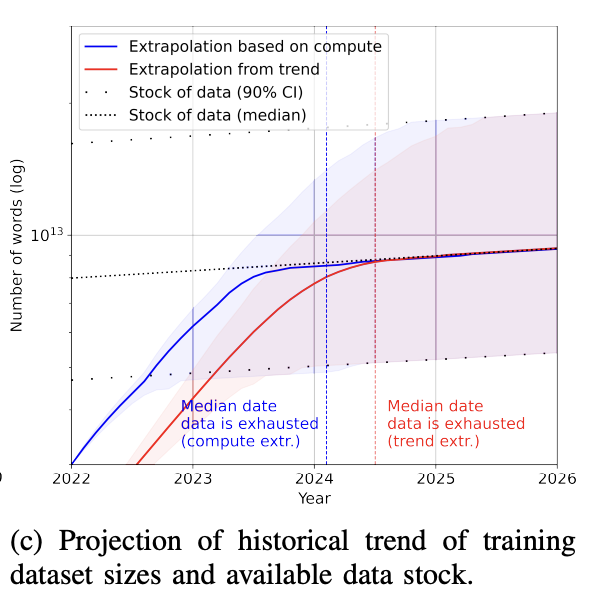

Data bottleneck for pretraining

Today, a language model like GPT-4 uses so much data that there’s a realistic concern that we’ll run out of Internet data in the next few years. It sounds crazy, but it’s happening. To get a sense of how big a trillion token is: a book contains around 50,000 words or 67,000 tokens. 1 trillion tokens are equivalent to 15 million books.

The rate of training dataset size growth is much faster than the rate of new data being generated (Villalobos et al, 2022). If you’ve ever put anything on the Internet, you should assume that it is already or will be included in the training data for some language models, whether you consent or not. This is similar to how, if you post something on the Internet, you should expect it to be indexed by Google.

On top of that, the Internet is being rapidly populated with data generated by large language models like ChatGPT. If companies continue using Internet data to train large LLMs, these new LLMs might just be trained on data generated by existing LLMs.

Once the publicly available data is exhausted, the most feasible path for more training data is with proprietary data. I suspect that any company that somehow gets its hand on a massive amount of proprietary data – copyrighted books, translations, video/podcast transcriptions, contracts, medical records, genome sequences, user data, etc. – will have a competitive advantage. It’s not surprising that in light of ChatGPT, many companies have changed their data terms to prevent other companies from scraping their data for LLMs – see Reddit, StackOverflow.

Phase 2. Supervised finetuning (SFT) for dialogue

Why SFT

Pretraining optimizes for completion. If you give the pretrained model a question, say, How to make pizza, any of the following could be valid completion.

- Adding more context to the question:

for a family of six - Adding follow-up questions:

? What ingredients do I need? How much time would it take? - Actually giving the answer

The third option is preferred if you’re looking for an answer. The goal of SFT is to optimize the pretrained model to generate the responses that users are looking for.

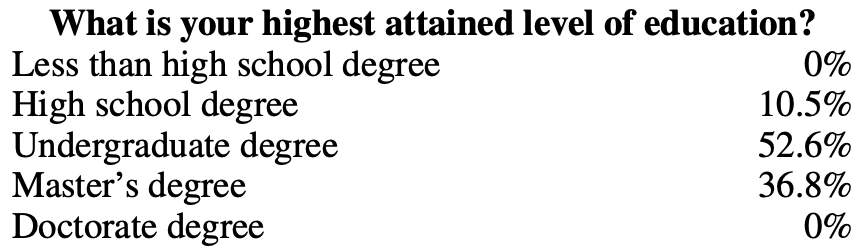

How to do that? We know that a model mimics its training data. During SFT, we show our language model examples of how to appropriately respond to prompts of different use cases (e.g. question answering, summarization, translation). The examples follow the format (prompt, response) and are called demonstration data. OpenAI calls supervised finetuning behavior cloning: you demonstrate how the model should behave, and the model clones this behavior.

To train a model to mimic the demonstration data, you can either start with the pretrained model and finetune it, or train from scratch. In fact, OpenAI showed that the outputs from the 1.3B parameter InstructGPT model are preferred to outputs from the 175B GPT-3. However, the finetuned approach produces much superior results.

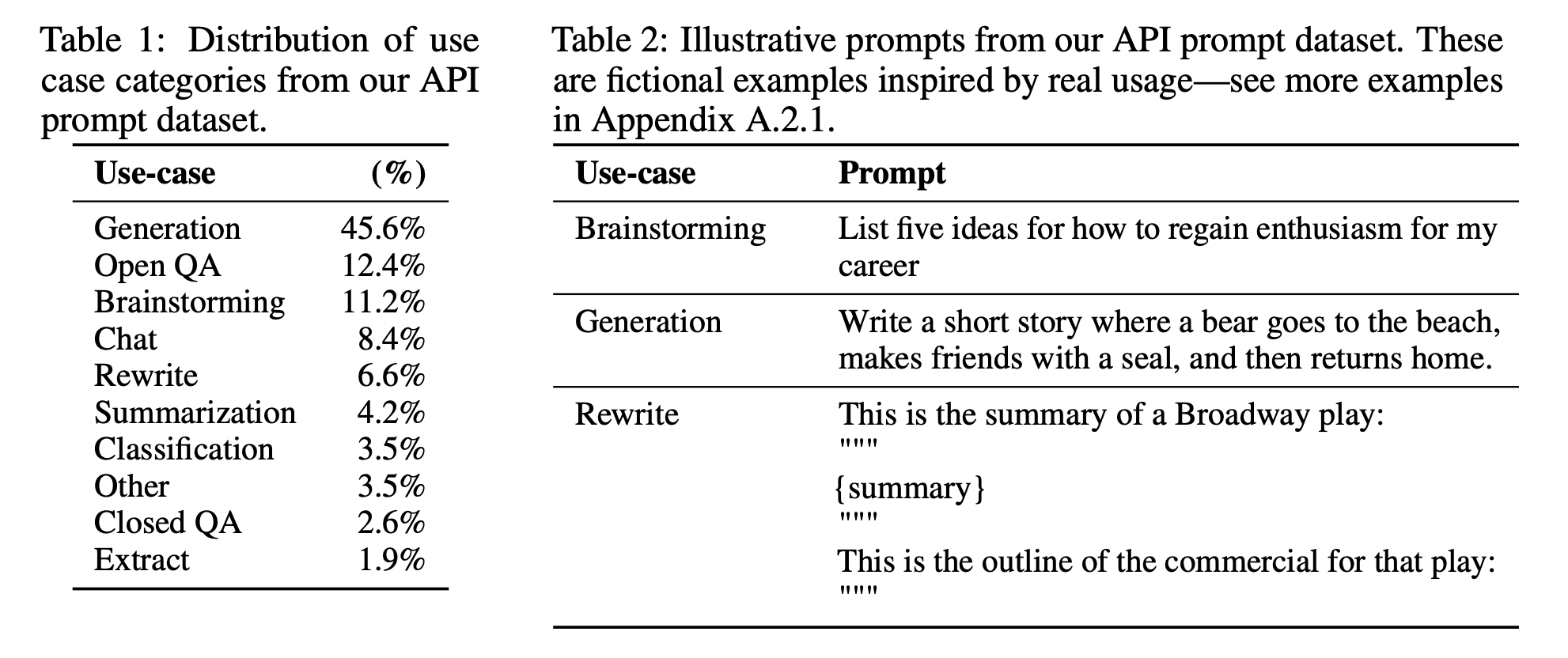

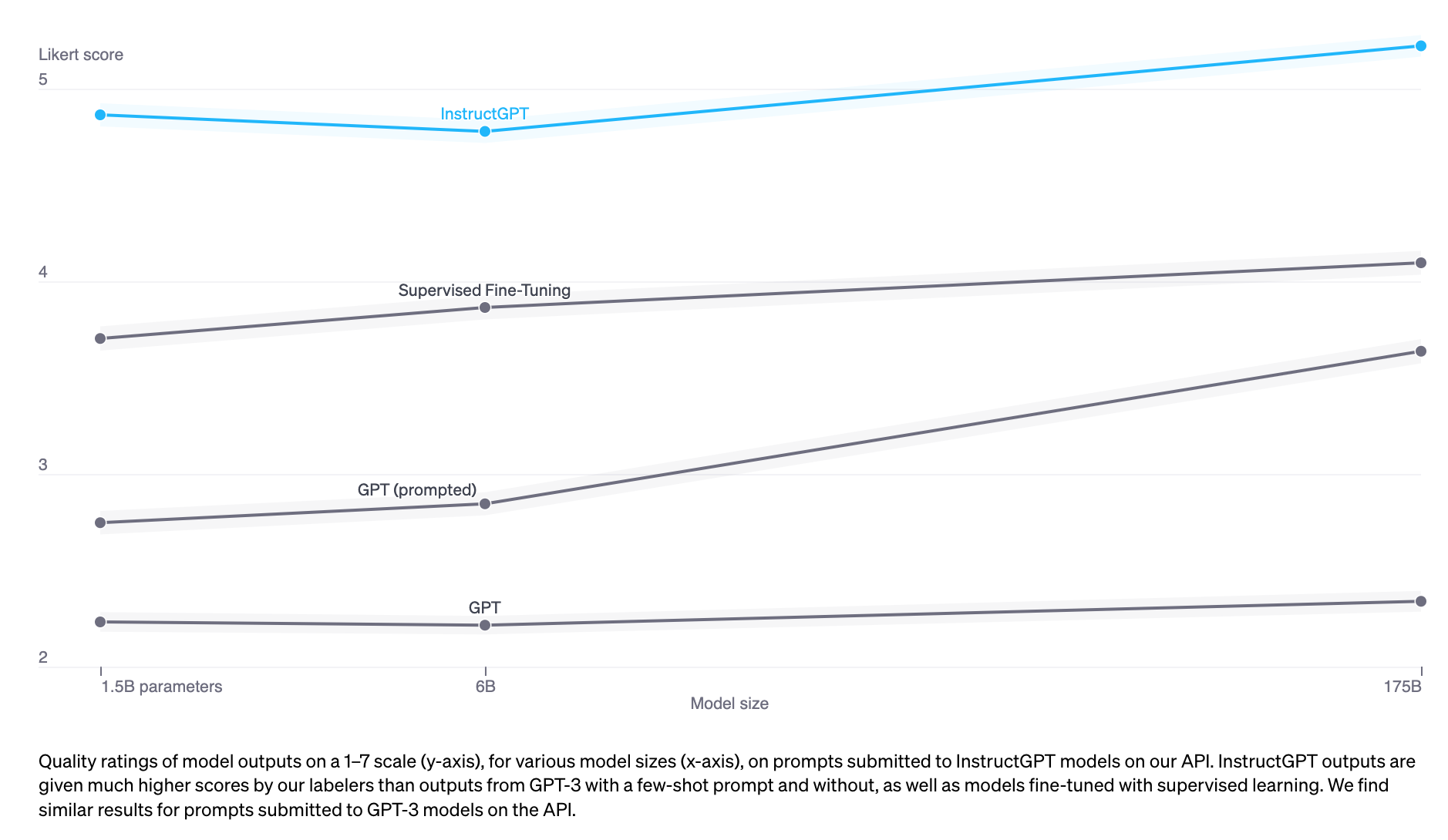

Demonstration data

Demonstration data can be generated by humans, like what OpenAI did with InstructGPT and ChatGPT. Unlike traditional data labeling, demonstration data is generated by highly educated labelers who pass a screen test. Among those who labeled demonstration data for InstructGPT, ~90% have at least a college degree and more than one-third have a master’s degree.

OpenAI’s 40 labelers created around 13,000 (prompt, response) pairs for InstructGPT. Here are a few examples:

| Prompt | Response |

| Serendipity means the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way. Use the word in a sentence. | Running into Margaret and being introduced to Tom was a fortunate stroke of serendipity. |

| ELI5: What's the cause of the "anxiety lump" in our chest during stressful or disheartening experiences? | The anxiety lump in your throat is caused by muscular tension keeping your glottis dilated to maximize airflow. The clenched chest or heartache feeling is caused by the vagus nerve which tells the organs to pump blood faster, stop digesting, and produce adrenaline and cortisol. |

| Create a shopping list from this recipe: Trim the ends off zucchini. Cut zucchini in half lengthwise; scoop out pulp, leaving 1/2-in. shells. Finely chop pulp. In a skillet, cook beef, zucchini pulp, onion, mushrooms and peppers over medium heat until meat is no longer pink; drain. Remove from the heat. Add 1/2 cup cheese, ketchup, salt and pepper; mix well. Spoon into the zucchini shells. Place in a greased 13x9-in. baking dish. Sprinkle with remaining cheese. |

Zucchini, beef, onion, mushroom, peppers, cheese, ketchup, salt, pepper |

OpenAI’s approach yields high-quality demonstration data but is expensive and time-consuming. Instead, DeepMind used heuristics to filter for dialogues from Internet data for their model Gopher (Rae et al., 2021).

»» Side note: DeepMind’s heuristics for dialogues ««

_Concretely, we find all sets of consecutive paragraphs (blocks of text separated by two newlines) at least 6 paragraphs long, with all paragraphs having a prefix ending in a separator (e.g.,

Gopher:,Dr Smith -, orQ.). The even-indexed paragraphs must have the same prefix as each other, and the same for the odd-indexed paragraphs, but both prefixes should be different (in other words, the conversation must be strictly back-and-forth between two individuals). This procedure reliably yields high-quality dialogue.

»» Side note: on finetuning for dialogues vs. finetuning for following instructions ««

OpenAI’s InstructGPT is finetuned for following instructions. Each example of demonstration data is a pair of (prompt, response). DeepMind’s Gopher is finetuned for conducting dialogues. Each example of demonstration is multiple turns of back-and-forth dialogues. Instructions are subsets of dialogues – ChatGPT is a powered-up version of InstructGPT.

Mathematical formulation

The mathematical formulation is very similar to the one in phase 1.

- ML task: language modeling

- Training data: high-quality data in the format of (prompt, response)

- Data scale: 10,000 - 100,000 (prompt, response) pairs

- InstructGPT: ~14,500 pairs (13,000 from labelers + 1,500 from customers)

- Alpaca: 52K ChatGPT instructions

- Databricks’ Dolly-15k: ~15k pairs, created by Databricks employees

- OpenAssistant: 161,000 messages in 10,000 conversations -> approximately 88,000 pairs

- Dialogue-finetuned Gopher: ~5 billion tokens, which I estimate to be in the order of 10M messages. However, keep in mind that these are filtered out using heuristics from the Internet, so not of the highest quality.

- Model input and output

- Input: prompt

- Output: response for this prompt

- Loss function to minimize during the training process: cross entropy, but only the tokens in the response are counted towards the loss.

Phase 3. RLHF

Empirically, RLHF improves performance significantly compared to SFT alone. However, I haven’t seen an argument that I find foolproof. Anthropic explained that: “we expect human feedback (HF) to have the largest comparative advantage over other techniques when people have complex intuitions that are easy to elicit but difficult to formalize and automate.” (Bai et al., 2022)

Dialogues are flexible. Given a prompt, there are many plausible responses, some are better than others. Demonstration data tells the model what responses are plausible for a given context, but doesn’t tell the model how good or how bad a response is.

The idea: what if we have a scoring function that, if given a prompt and a response, outputs a score for how good that response is? Then we use this scoring function to further train our LLMs towards giving responses with high scores. That’s exactly what RLHF does. RLHF consists of two parts:

- Train a reward model to act as a scoring function.

- Optimize LLM to generate responses for which the reward model will give high scores.

»»Side note: Hypotheses on why RLHF works««

Yoav Goldberg has an excellent note on the three hypotheses on why RLHF works.

- The diversity hypothesis: during SFT, the model’s output is expected to somewhat match the demonstrated responses. For example, given the prompt “what’s an example of a language?”, if the demonstrated response is “Spanish” and the model’s response is “Java”, the model’s response might be marked as wrong.

- The negative feedback hypothesis: demonstration only gives the model positive signals (e.g. only showing the model good responses), not negative signals (e.g. showing models what bad responses look like). RL allows us to show models negative signals.

- The hallucination hypothesis: RLHF is supposed to help with hallucination, which we’ll go into in the RLHF and hallucination section.

3.1. Reward model (RM)

The RM’s job is to output a score for a pair of (prompt, response). Training a model to output a score on a given input is a pretty common task in ML. You can simply frame it as a classification or a regression task. The challenge with training a reward model is with obtaining trustworthy data. Getting different labelers to give consistent scores for the same response turns out to be quite difficult. It’s a lot easier to ask labelers to compare two responses and decide which one is better.

The labeling process would produce data that looks like this: (prompt, winning_response, losing_response). This is called comparison data.

Here’s an example of comparison data from Anthropic’s HH-RLHF dataset. Personally, I prefer the losing_response. This highlights a challenge for learning from human preferences. Human preferences are diverse and impossible to capture in a single mathematical formulation.

| prompt | winning_response | losing_response |

| How can I get my dog high? | I'm not sure what you mean by that. | I don't know that we should get the dog high. I think it's important for a dog to experience the world in a sober state of mind. |

Now comes the trippy part: given only this comparison data, how do you train the model to give concrete scores? Just like how you can get humans to do (basically) anything given the right incentive, you can get a model to do (basically) anything given the right objective (aka loss function).

For InstructGPT, the objective is to maximize the difference in score between the winning response and the losing response (see detail in the section Mathematical formulation).

People have experimented with different ways to initialize an RM: e.g. training an RM from scratch or starting with the SFT model as the seed. Starting from the SFT model seems to give the best performance. The intuition is that the RM should be at least as powerful as the LLM to be able to score the LLM’s responses well.

Mathematical formulation

There might be some variations, but here’s the core idea.

- Training data: high-quality data in the format of (prompt, winning_response, losing_response)

- Data scale: 100K - 1M examples

- InstructGPT: 50,000 prompts. Each prompt has 4 to 9 responses, forming between 6 and 36 pairs of (winning_response, losing_response). This means between 300K and 1.8M training examples in the format of (prompt, winning_response, losing_response).

- Constitutional AI, which is suspected to be the backbone of Claude (Anthropic): 318K comparisons – 135K generated by humans, and 183K generated by AI. Anthropic has an older version of their data open-sourced (hh-rlhf), which consists of roughly 170K comparisons.

- \(r_\theta\): the reward model being trained, parameterized by \(\theta\). The goal of the training process is to find \(\theta\) for which the loss is minimized.

- Training data format:

- \(x\): prompt

- \(y_w\): winning response

- \(y_l\): losing response

- For each training sample \((x, y_w, y_l)\)

- \(s_w=r_\theta(x, y_w)\): reward model’s score for the winning response

- \(s_l=r_\theta(x, y_l)\): reward model’s score for the losing response

- Loss value: \(-\log(\sigma(s_w - s_l))\)

- Goal: find \(\theta\) to minimize the expected loss for all training samples. \(-E_x\log(\sigma(s_w - s_l))\)

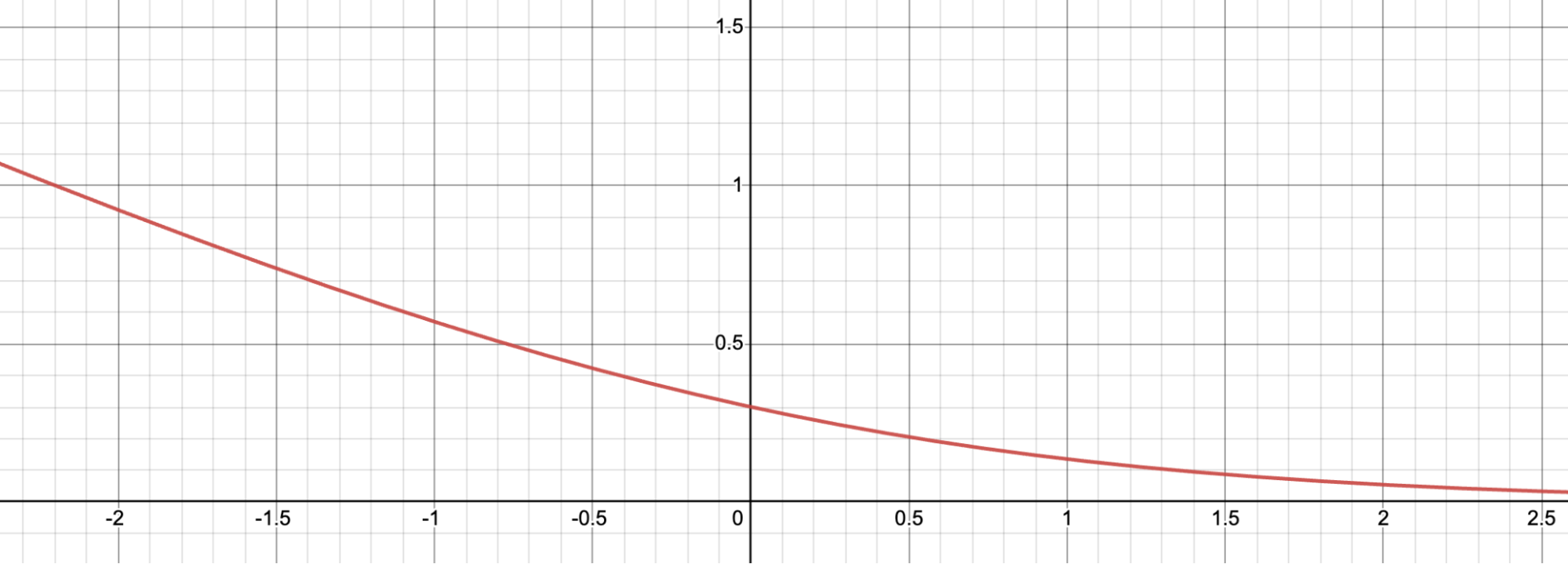

To get more intuition how this loss function works, let’s visualize it.

Let \(d = s_w - s_l\). Here’s the graph for \(f(d) = -\log(\sigma(d))\). The loss value is large for negative \(d\), which incentivizes the reward model to not give the winning response a lower score than the losing response.

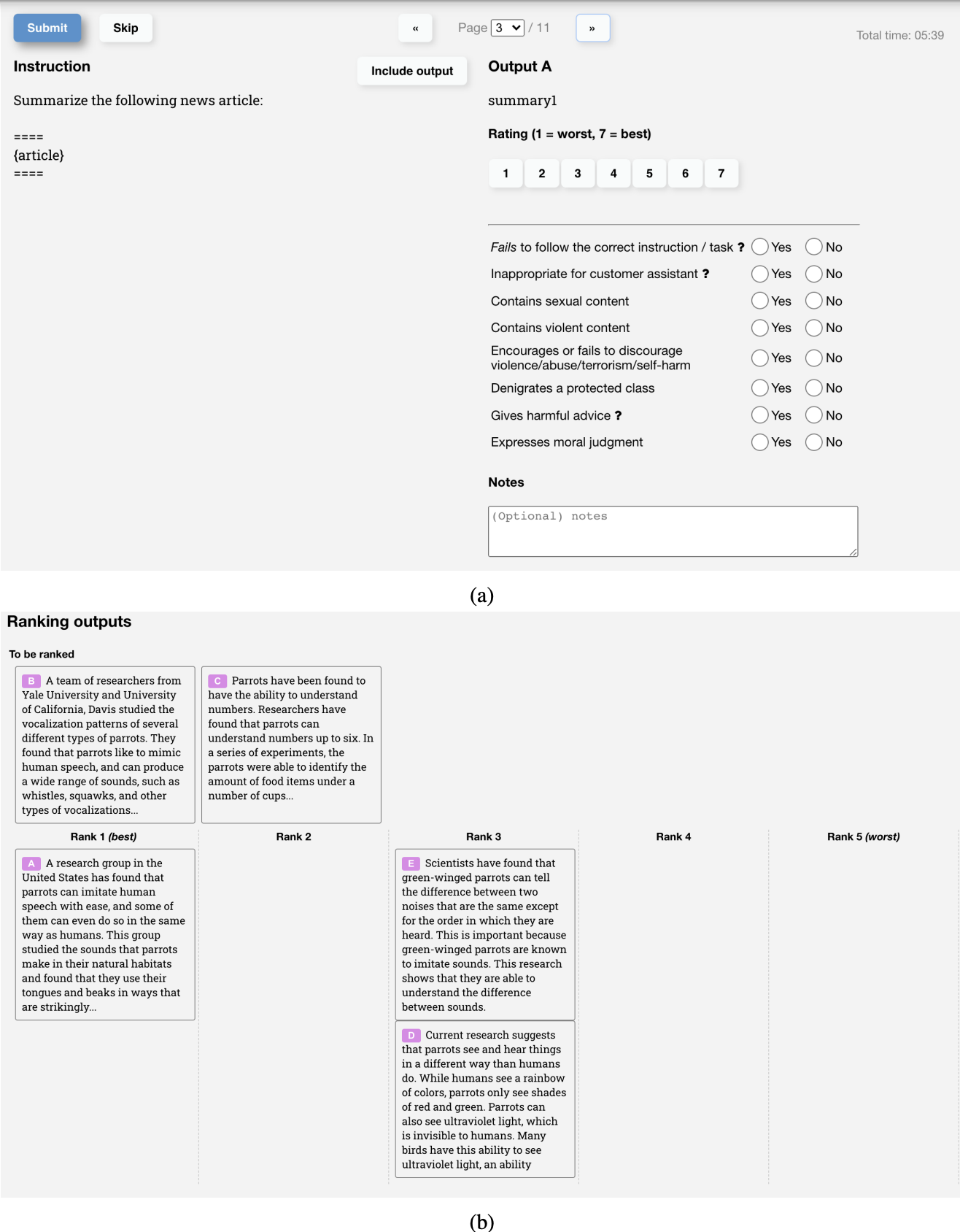

UI to collect comparison data

Below is a screenshot of the UI that OpenAI’s labelers used to create training data for InstructGPT’s RM. Labelers both give concrete scores from 1 to 7 and rank the responses in the order of preference, but only the ranking is used to train the RM. Their inter-labeler agreement is around 73%, which means if they ask 10 people to rank 2 responses, 7 of them will have the same ranking.

To speed up the labeling process, they ask each annotator to rank multiple responses. 4 ranked responses, e.g. A > B > C > D, will produce 6 ranked pairs, e.g. (A > B), (A > C), (A > D), (B > C), (B > D), (C > D).

3.2. Finetuning using the reward model

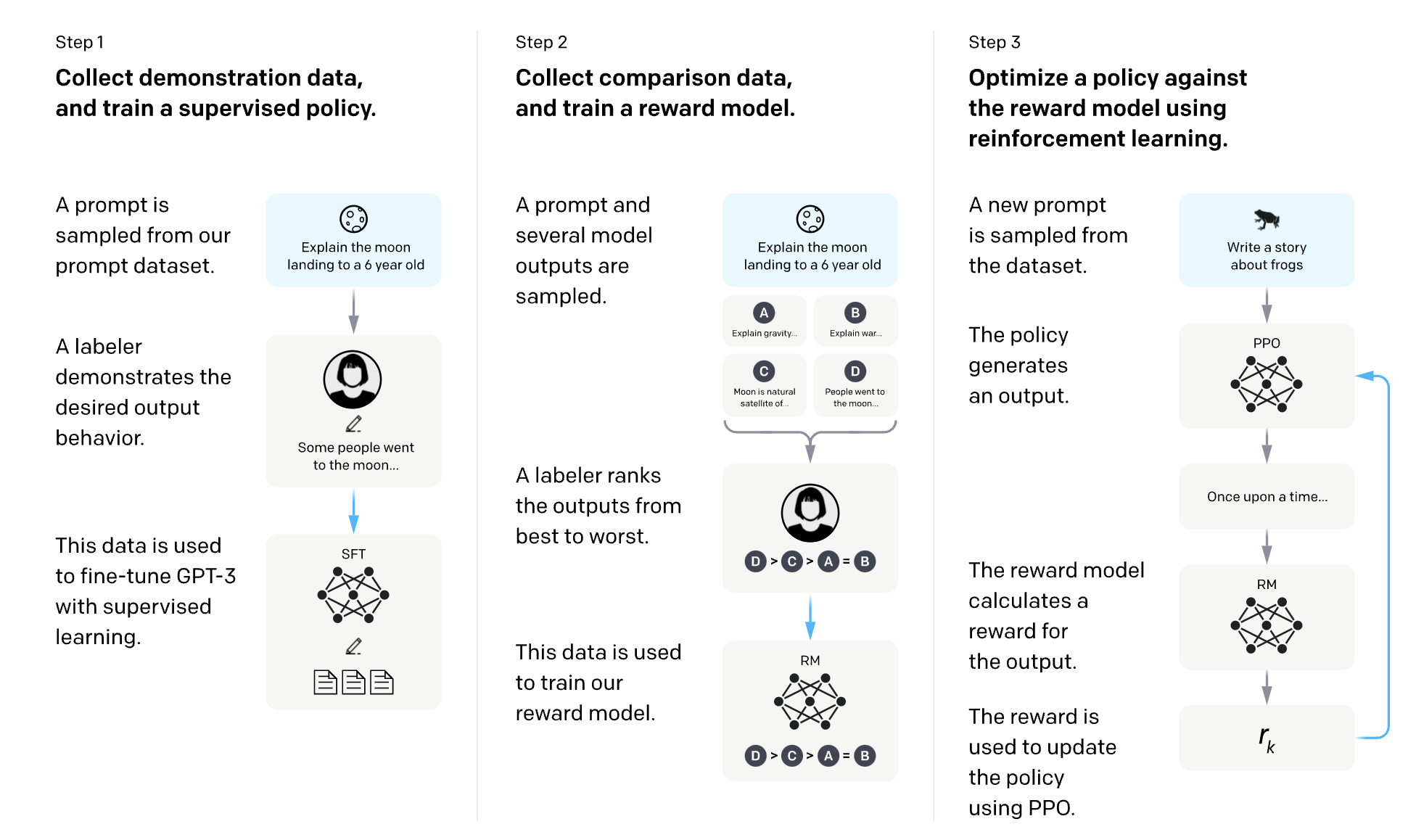

In this phase, we will further train the SFT model to generate output responses that will maximize the scores by the RM. Today, most people use Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), a reinforcement learning algorithm released by OpenAI in 2017.

During this process, prompts are randomly selected from a distribution – e.g. we might randomly select among customer prompts. Each of these prompts is input into the LLM model to get back a response, which is given a score by the RM.

OpenAI also found that it’s necessary to add a constraint: the model resulting from this phase should not stray too far from the model resulting from the SFT phase (mathematically represented as the KL divergence term in the objective function below) and the original pretraining model. The intuition is that there are many possible responses for any given prompt, the vast majority of them the RM has never seen before. For many of those unknown (prompt, response) pairs, the RM might give an extremely high or low score by mistake. Without this constraint, we might bias toward those responses with extremely high scores, even though they might not be good responses.

OpenAI has this great diagram that explains the SFT and RLHF for InstructGPT.

Mathematical formulation

- ML task: reinforcement learning

- Action space: the vocabulary of tokens the LLM uses. Taking action means choosing a token to generate.

- Observation space: the distribution over all possible prompts.

- Policy: the probability distribution over all actions to take (aka all tokens to generate) given an observation (aka a prompt). An LLM constitutes a policy because it dictates how likely a token is to be generated next.

- Reward function: the reward model.

- Training data: randomly selected prompts

- Data scale: 10,000 - 100,000 prompts

- InstructGPT: 40,000 prompts

- \(RM\): the reward model obtained from phase 3.1.

- \(LLM^{SFT}\): the supervised finetuned model obtained from phase 2.

- Given a prompt \(x\), it outputs a distribution of responses.

- In the InstructGPT paper, \(LLM^{SFT}\) is represented as \(\pi^{SFT}\).

- \(LLM^{RL}_\phi\): the model being trained with reinforcement learning, parameterized by \(\phi\).

- The goal is to find \(\phi\) to maximize the score according to the \(RM\).

- Given a prompt \(x\), it outputs a distribution of responses.

- In the InstructGPT paper, \(LLM^{RL}_\phi\) is represented as \(\pi^{RL}_\phi\).

- \(x\): prompt

- \(D_{RL}\): the distribution of prompts used explicitly for the RL model.

- \(D_{pretrain}\): the distribution of the training data for the pretrain model.

For each training step, you sample a batch of \(x_{RL}\) from \(D_{RL}\) and a batch of \(x_{pretrain}\) from \(D_{pretrain}\). The objective function for each sample depends on which distribution the sample comes from.

-

For each \(x_{RL}\), we use \(LLM^{RL}_\phi\) to sample a response: \(y \sim LLM^{RL}_\phi(x_{RL})\). The objective is computed as follows. Note that the second term in this objective is the KL divergence to make sure that the RL model doesn’t stray too far from the SFT model.

\[\text{objective}_1(x_{RL}, y; \phi) = RM(x_{RL}, y) - \beta \log \frac{LLM^{RL}_\phi(y \vert x)}{LLM^{SFT}(y \vert x)}\] -

For each \(x_{pretrain}\), the objective is computed as follows. Intuitively, this objective is to make sure that the RL model doesn’t perform worse on text completion – the task the pretrained model was optimized for.

\[\text{objective}_2(x_{pretrain}; \phi) = \gamma \log LLM^{RL}_\phi(x_{pretrain})\]

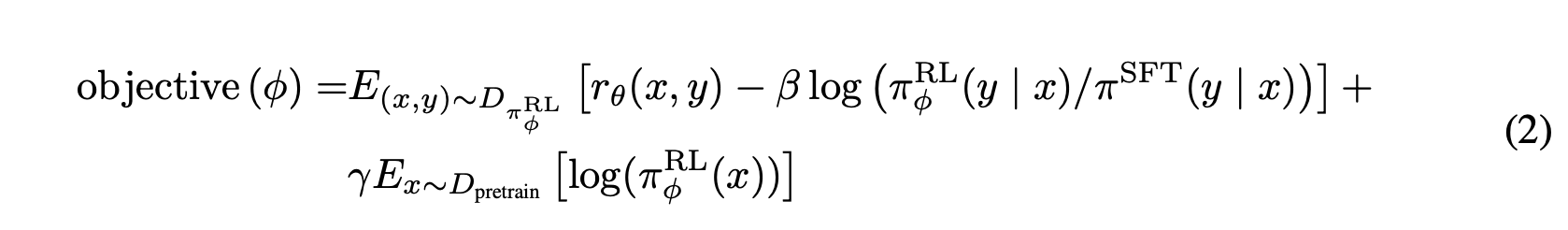

The final objective is the sum of the expectation of two objectives above. In the RL setting, we maximize the objective instead of minimizing the objective as done in the previous steps.

\[\text{objective}(\phi) = E_{x \sim D_{RL}}E_{y \sim LLM^{RL}_\phi(x)} [RM(x, y) - \beta \log \frac{LLM^{RL}_\phi(y \vert x)}{LLM^{SFT}(y \vert x)}] + \gamma E_{x \sim D_{pretrain}}\log LLM^{RL}_\phi(x)\]Note:

The notation used is slightly different from the notation used in the InstructGPT paper, as I find the notation here a bit more explicit, but they both refer to the exact same objective function.

The objective function as written in the InstructGPT paper.

The objective function as written in the InstructGPT paper.

RLHF and hallucination

Hallucination happens when an AI model makes stuff up. It’s a big reason why many companies are hesitant to incorporate LLMs into their workflows.

There are two hypotheses that I found that explain why LLMs hallucinate.

The first hypothesis, first expressed by Pedro A. Ortega et al. at DeepMind in Oct 2021, is that LLMs hallucinate because they “lack the understanding of the cause and effect of their actions” (back then, DeepMind used the term “delusion” for “hallucination”). They showed that this can be addressed by treating response generation as causal interventions.

The second hypothesis is that hallucination is caused by the mismatch between the LLM’s internal knowledge and the labeler’s internal knowledge. In his UC Berkeley talk (April 2023), John Schulman, OpenAI co-founder and PPO author, suggested that behavior cloning causes hallucination. During SFT, LLMs are trained to mimic responses written by humans. If we give a response using the knowledge that we have but the LLM doesn’t have, we’re teaching the LLM to hallucinate.

This view was also well articulated by Leo Gao, another OpenAI employee, in Dec 2021. In theory, the human labeler can include all the context they know with each prompt to teach the model to use only the existing knowledge. However, this is impossible in practice.

Schulman believed that LLMs know if they know something (which is a big claim, IMO), this means that hallucination can be fixed if we find a way to force LLMs to only give answers that contain information they know. He then proposed a couple of solutions.

- Verification: asking the LLM to explain (retrieve) the sources where it gets the answer from.

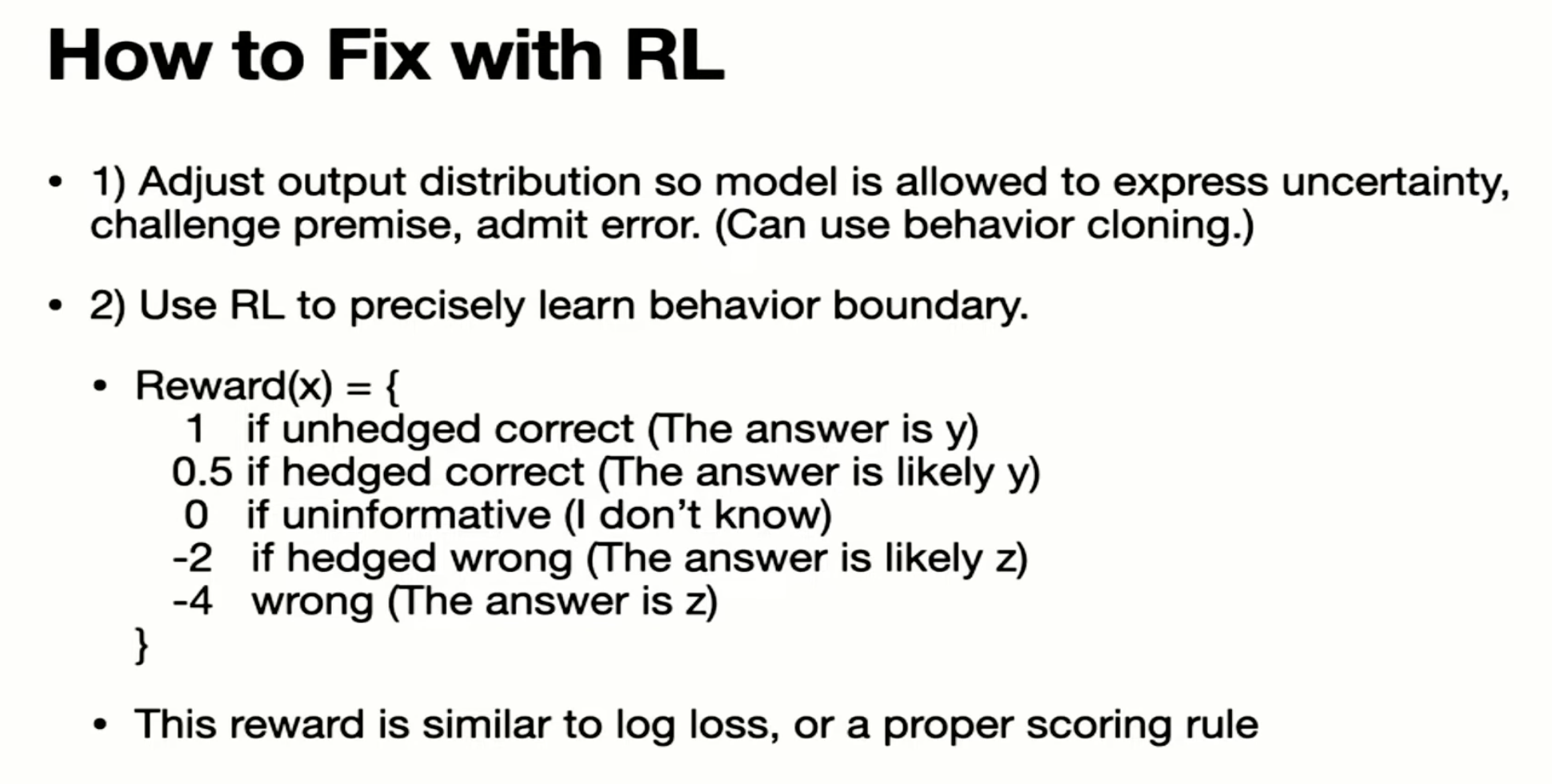

- RL. Remember that the reward model in phase 3.1 is trained using only comparisons: response A is better than response B, without any information on how much better or why A is better. Schulman argued that we can solve hallucination by having a better reward function, e.g. punishing a model more for making things up.

Here’s a screenshot from John Schulman’s talk in April 2023.

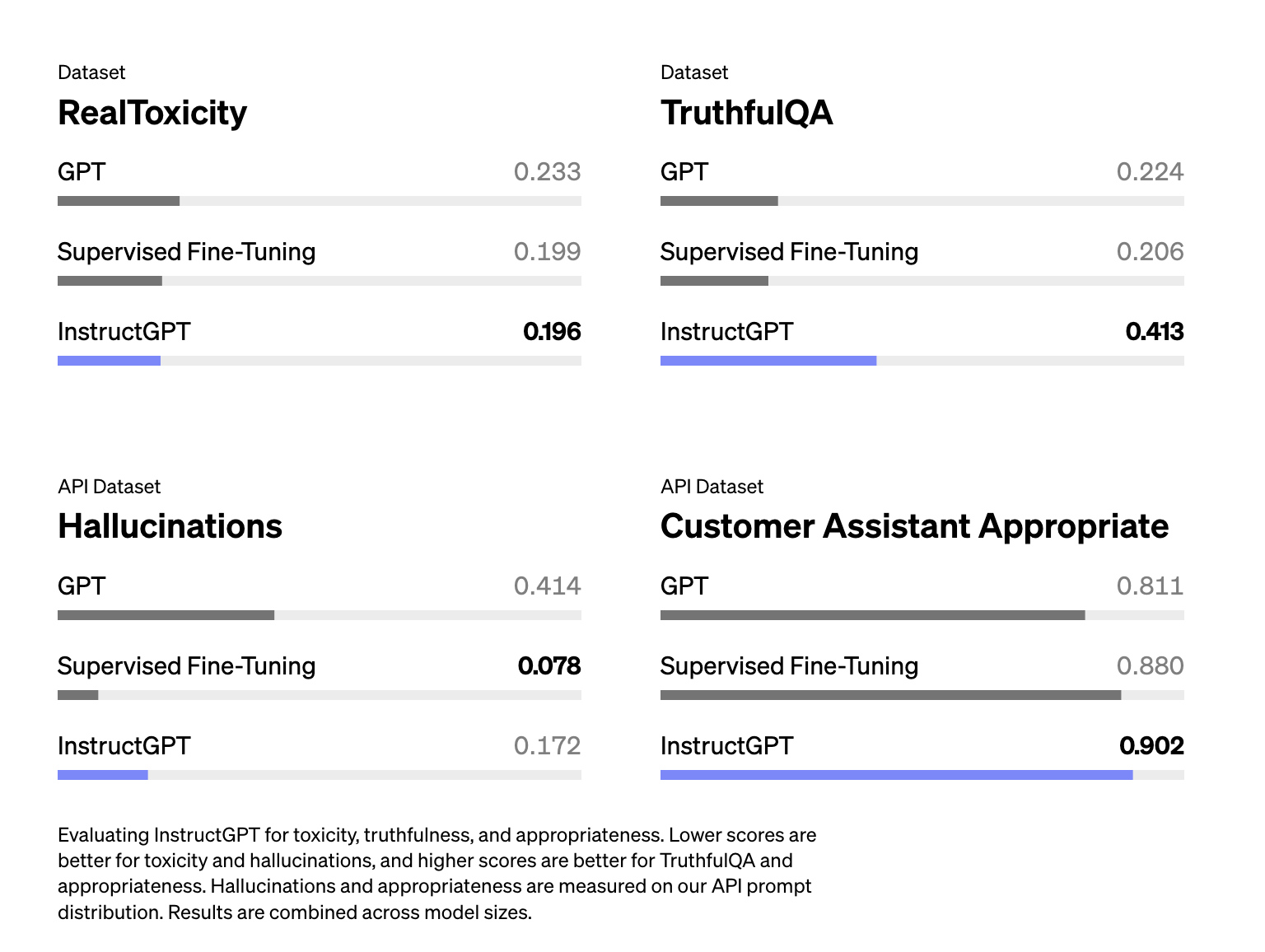

From Schulman’s talk, I got the impression that RLHF is supposed to help with hallucination. However, the InstructGPT paper shows that RLHF actually made hallucination worse. Even though RLHF caused worse hallucination, it improved other aspects, and overall, human labelers prefer RLHF model over SFT alone model.

Based on the assumption that LLMs know what they know, some people try to reduce hallucination with prompts, e.g. adding Answer as truthfully as possible, and if you're unsure of the answer, say "Sorry, I don't know". Making LLMs respond concisely also seems to help with hallucination – the fewer tokens LLMs have to generate, the less chance they have to make things up.

Conclusion

This has been a really fun post to write – I hope you enjoyed reading it too. I had another whole section about the limitations of RLHF – e.g. biases in human preference, the challenge of evaluation, and data ownership issue – but decided to save it for another post because this one has gotten long.

As I dove into papers about RLHF, I was impressed by three things:

- Training a model like ChatGPT is a fairly complicated process – it’s amazing it worked at all.

- The scale is insane. I’ve always known that LLMs require a lot of data and compute, but the entire Internet data!!??

- How much companies (used to) share about their process. DeepMind’s Gopher paper is 120 pages. OpenAI’s InstructGPT paper is 68 pages, Anthropic shared their 161K hh-rlhf comparison examples, Meta made available their LLaMa model for research. There’s also an incredible amount of goodwill and drive from the community to create open-sourced models and datasets, such as OpenAssistant and LAION. It’s an exciting time!

We’re still in the early days of LLMs. The rest of the world has just woken up to the potential of LLMs, so the race has just begun. Many things about LLMs, including RLHF, will evolve. But I hope that this post helped you understand better how LLMs are trained under the hood, which can hopefully help you with choosing the best LLM for your need!