Design a machine learning system

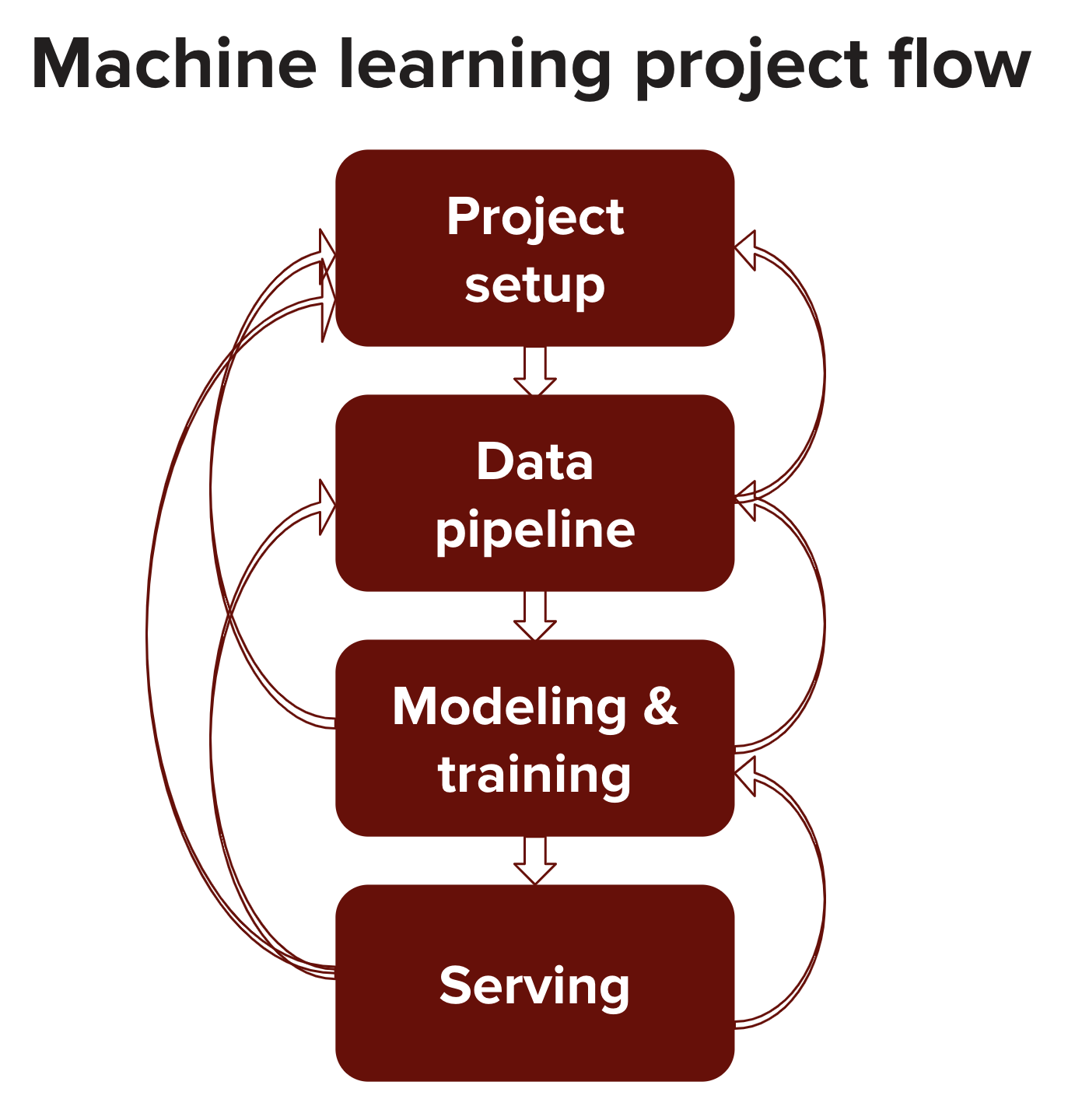

Designing a machine learning system is an iterative process. There are generally four main components of the process: project setup, data pipeline, modeling (selecting, training, and debugging your model), and serving (testing, deploying, maintaining).

The output from one step might be used to update the previous steps. Some scenarios:

- After examining the available data, you realize it's impossible to get the data needed to solve the problem you previously defined, so you have to frame the problem differently.

- After training, you realize that you need more data or need to re-label your data.

- After serving your model to the initial users, you realize that the way they use your product is very different from the assumptions you made when training the model, so you have to update your model.

When asked to design a machine learning system, you need to consider all of these components.

Project setup

Before you even say neural network, you should first figure out as much detail about the problem as possible.

- Goals: What do you want to achieve with this problem? For example, if you're asked to create a system to rank what activities to show first in one's newsfeed on Facebook, some of the possible goals are: to minimize the spread of misinformation, to maximize revenue from sponsored content, or to maximize users' engagement.

- User experience: Ask your interviewer for a step by step walkthrough of how end users are supposed to use the system. If you're asked to predict what app a phone user wants to use next, you might want to know when and how the predictions are used. Do you only show predictions only when a user unlocks their phone or during the entire time they're on their phone?

- Performance constraints: How fast/good does the prediction have to be? What's more important: precision or recall? What's more costly: false negative or false positive? For example, if you build a system to predict whether someone is vulnerable to certain medical problems, your system must not have false negatives. However, if you build a system to predict what word a user will type next on their phone, it doesn't need to be perfect to provide value to users.

- Evaluation: How would you evaluate the performance of your system, during both training and inferencing? During inferencing, a system's performance might be inferred from users' reactions, e.g. how many times they choose the system's suggestions. If this metric isn't differentiable, you need another metric to use during training, e.g. the loss function to optimize. Evaluation can be very difficult for generative models. For example, if you're asked to build a dialogue system, how do you evaluate your system's responses?

- Personalization: How personalized does your model have to be? Do you need one model for all the users, for a group of users, or for each user individually? If you need multiple models, is it possible to train a base model on all the data and finetune it for each group or each user?

- Project constraints: These are the constraints that you have to worry about in the real world but less so during interviews: how much time you have until deployment, how much compute power is available, what kind of talents work on the project, what available systems can be used, etc.

Resources

Data pipeline

In school, you work with available, clean datasets and can spend most of your time on building and training machine learning models. In industry, you probably spend most of your time collecting, annotating, and cleaning data. When teaching, I noticed that many students shied away from data wrangling as they considered it uncool, the way a backend engineer sometimes considers frontend uncool, but the reality is that employers value highly both frontend and data wrangling abilities.

As machine learning is driven more by data than by algorithms, for every formulation of the problem that you propose, you should also tell your interviewer what kind of data and how much data you need: both for training and for evaluating your systems.

You need to specify the input and output of your system. There are many different ways to frame a problem. Consider the app prediction problem above. A naive setup would be to have a user profile (age, gender, ethnicity, occupation, income, technical savviness, etc.) and environment profile (time, location, previous apps used, etc.) as input and output a probability distribution for every single app available. This is a bad approach because there are too many apps and when a new app is added, you have to retrain your model. A better approach is to have the user profile, the environment, and the app profile as input, and output a binary classification whether it's a match or not.

Some of the questions you should ask your interviewer:

- Data availability and collection: What kind of data is available? How much data do you already have? Is it annotated and if so, how good is the annotation? How expensive is it to get the data annotated? How many annotators do you need for each sample? How to resolve annotators' disagreements? What's their data budget? Can you utilize any of the weakly supervised or unsupervised methods to automatically create new annotated data from a small amount of humanly annotated data?

- User data: What data do you need from users? How do you collect it? How do you get users' feedback on the system, and if you want to use that feedback to improve the system online or periodically?

- Storage: Where is the data currently stored: on the cloud, local, or on the users' devices? How big is each sample? Does a sample fit into memory? What data structures are you planning on using for the data and what are their tradeoffs? How often does the new data come in?

- Data preprocessing & representation: How do you process the raw data into a form useful for your models? Will you have to do any featuring engineering or feature extraction? Does it need normalization? What to do with missing data? If there's class imbalance in the data, how do you plan on handling it? How to evaluate whether your train set and test set come from the same distribution, and what to do if they don't? If you have data of different types, say both texts, numbers, and images, how are you planning on combining them?

- Challenges: Handling user data requires extra care, as any of the many companies that have got into trouble for user data mishandling can tell you.

- Privacy: What privacy concerns do users have about their data? What anonymizing methods do you want to use on their data? Can you store users' data back to your servers or can only access their data on their devices?

- Biases: What biases might represent in the data? How would you correct the biases? Are your data and your annotation inclusive? Will your data reinforce current societal biases?

Resources

- More data usually beats better algorithms by Anand Rajaraman, Datawocky, 2008.

Modeling

Modeling, including model selection, training, and debugging, is what's often covered in most machine learning courses. However, it's only a small component of the entire process. Some might even argue that it's the easiest component.

Model selection

Most problems can be framed as one of the common machine learning tasks, so familiarity with common machine learning tasks and the typical approaches to solve them will be very useful. You should first figure out the category of the problem. Is it supervised or unsupervised? Is it regression or classification? Does it require generation or only prediction? If generation, your models will have to learn the latent space of your data, which is a much harder task than just prediction.

Note that these "or" aren't mutually exclusive. An income prediction task can be regression if we output raw numbers, but if we quantize the income into different brackets and predict the bracket, it becomes a classification problem. Similarly, you can use unsupervised learning to learn labels for your data, then use those labels for supervised learning.

Then you can frame the question as a specific task: object recognition, text classification, time series analysis, recommender systems, dimensionality reduction, etc. Keep in mind that there are many ways to frame a problem, and you might not know which way works better until you've tried to train some models.

When searching for a solution, your goal isn't to show off your knowledge of the latest buzzwords but to use the simplest solution that can do the job. Simplicity serves two purposes. First, gradually adding more complex components makes it easier to debug step by step. Second, the simplest model serves as a baseline to which you can compare your more complex models.

Setting up an appropriate baseline is an important step that many candidates forget. There are three different baselines that you should think about:

- Random baseline: if your model just predicts everything at random, what's the expected performance?

- Human baseline: how well would humans perform on this task?

- Simple heuristic: for example, for the task of recommending the app to use next on your phone, the simplest model would be to recommend your most frequently used app. If this simple heuristic can predict the next app accurately 70% of the time, any model you build has to outperform it significantly to justify the added complexity.

Your first step to approaching any problem is to find its effective heuristics. Martin Zinkevich, a research scientist at Google, explained in his handbook Rules of Machine Learning: Best Practices for ML Engineering that "if you think that machine learning will give you a 100% boost, then a heuristic will get you 50% of the way there." However, resist the trap of increasingly complex heuristics. If your system has more than 100 nested if-else, it's time to switch to machine learning.

When considering machine learning models, don't forget that non-deep learning models exist. Deep learning models are often expensive to train and hard to explain. Most of the time, in production, they are only useful if their performance is unquestionably superior. For example, for the task of classification, before using a transformer-based model with 300 million parameters, see if a decision tree works. For fraud detection, before wielding complex neural networks, try one of the many popular non-neural network approaches such as k-nearest neighbor classifier.

Most real world problems might not even need deep learning. Deep learning needs data, and to gather data, you might first need users. To avoid the catch-22, you might want to launch your product without deep learning to gather user data to train your system.

Resources

- Machine Learning Algorithms: Which One to Choose for Your Problem by Daniil Korbut, Stats and Bots, 2017.

Training

You should be able to anticipate what problems might arise during training and address them. Some of the common problems include: the training loss doesn't decrease, overfitting, underfitting, fluctuating weight values, dead neurons, etc. These problems are covered in the Regularization and training techniques, Optimization, and Activations sections in Chapter 9: Deep Learning.

Debugging

Have you ever experienced the euphoria of having your model work flawlessly on the first run? Neither have I. Debugging a machine learning model is hard, so hard that poking fun at how incompetent we are at debugging machine learning models has become a sport.

There are many reasons that can cause a model to perform poorly:

- Theoretical constraints: e.g. wrong assumptions, poor model/data fit.

- Poor model implementation: the more components a model has, the more things that can go wrong, and the harder it is to figure out which goes wrong.

- Snobby training techniques: e.g. call

model.train()instead ofmodel.eval()during evaluation. - Poor choice of hyperparameters: with the same implementation, a set of hyperparameters can give you the state-of-the-art result but another set of hyperparameters might never converge.

- Data problems: mismatched inputs/labels, over-preprocessed data, noisy data, etc.

Most of the bugs in deep learning are invisible. Your code compiles, the loss decreases, but your model doesn't learn anything or might never reach the performance it's supposed to. Having a procedure for debugging and having the discipline to follow that principle are crucial in developing, implementing, and deploying machine learning models.

During interviews, the interviewer might test your debugging skills by either giving you a piece of buggy code and ask you to fix it, or ask you about steps you'd take to minimize the opportunities for bugs to proliferate. There is, unfortunately, still no scientific approach to debugging in machine learning. However, there have been a number tried-and-true debugging techniques published by experienced machine learning engineers and researchers. Here are some of the steps you can take to ensure the correctness of your model.

-

Start simple and gradually add more components

Start with the simplest model and then slowly add more components to see if it helps or hurts the performance. For example, if you want to build a recurrent neural network (RNN), start with just one level of RNN cell before stacking multiple together, or adding more regularization. If you want to use a BERT-like model (Devlin et al., 2018) which uses both masked language model (MLM) and next sentence prediction loss (NSP), you might want to use only the MLM loss before adding NSP loss.

Currently, many people start out by cloning an open-source implementation of a state-of-the-art model and plugging in their own data. On the off-chance that it works, it's great. But if it doesn't, it's very hard to debug the system because the problem could have been caused by any of the many components in the model.

-

Overfit a single batch

After you have a simple implementation of your model, try to overfit a small amount of training data and run evaluation on the same data to make sure that it gets to the smallest possible loss. If it's for image recognition, overfit on 10 images and see if you can get to the accuracy to be 100%, or if it's for machine translation, overfit on 100 sentence pairs and see if you can get to the BLEU score of near 100. If it can't overfit a small amount of data, there's something wrong with your implementation.

-

Set a random seed

There are so many factors that contribute to the randomness of your model: weight initialization, dropout, data shuffling, etc. Randomness makes it hard to compare results across different experiments -- you have no idea if the change in performance is due to a change in the model or a different random seed. Setting a random seed ensures consistency between different runs. It also allows you to reproduce errors and other people to reproduce your results.

Resources

- Troubleshooting Deep Neural Networks: A Field Guide to Fixing Your Model. Josh Tobin, 2018.

- Things I wish we had known before we started our first Machine Learning project. Aseem Bansal, towards-infinity, 2018.

- How to unit test machine learning code by Chase Roberts, 2017

- A Recipe for Training Neural Networks. Andrej Karpathy, 2019.

- Practical Advice for Building Deep Neural Networks. Matt Holt and Daniel Ricks, BYU's Perception, Control and Cognition Laboratory, 2017.

- Top 6 errors novice machine learning engineers make. Christopher Dossman, AI³ | Theory, Practice, Business, 2017.

Hyperparameter tuning

With different sets of hyperparameters, the same model can give drastically different performance on the same dataset. Melis et al. showed in their 2018 paper On the State of the Art of Evaluation in Neural Language Models that weaker models with well-tuned hyperparameters can outperform stronger, more recent models.

Despite knowing its importance, people without real-world experience often ignore systematic approaches to hyperparameter tuning in favor of manual, gut-feeling approach. The most popular method is arguably Graduate Student Descent (GSD), a technique in which a graduate student plays around with the hyperparameters until the model works (GSD is a well-documented technique, see here, here, here, and here).

There have been a lot of research done on hyperparameter search algorithms, as well as tools to help you automatically search for a good set of hyperparameters. You might want to check out some of the popular methods for hyperparameter tuning including random search, grid search, Bayesian optimization. The book AutoML: Methods, Systems, Challenges by the AutoML group at the University of Freiburg dedicates its first chapter to hyperparameter optimization, which you can read online for free here.

The performance of each set of hyperparameters is evaluated on the validation set. Keep in mind that not all hyperparameters are created equal. A model's performance might be more sensitive to the change in one hyperparameter, and there have also been research done on accessing the importance of different hyperparameters.

Scaling

As models are getting bigger and more resource-intensive, companies care a lot more about training at scale. It's usually not listed as requirements since expertise in scalability is hard to acquire without regular access to massive compute resources. For machine learning engineering roles, you'll get huge bonus points if you're familiar with common scalability challenges and solutions. Scalability is an elaborate topic that merits its own book. This section covers some common issues, but scratches only the surface.

It's not uncommon to train a model with a dataset that can't be fit into the main memory. This is especially common when dealing with medical data such as CT scans or genome sequences. If you run into a situation like this, you should know how to preprocess (e.g. zero-centering, normalizing, whitening), shuffle, and batch your data when it doesn't fit into memory. When each sample of your data is too large, your model can handle a very small batch size, which can lead to instability for stochastic gradient descent based optimization.

On a very rare case, each sample is so large a single sample can't even fit into the memory, you will have to use techniques such as gradient checkpointing, a technique that leverages the memory footprint/computation tradeoff to make your system do more computation but require less memory. You can use an open-source package gradient-checkpointing developed by by Tim Salimans and Yaroslav Bulatov. According to the authors of the package, "for feed-forward model, we were able to fit more than 10x larger models onto our GPU, at only a 20% increase in computation time."

It's almost the norm now for machine learning engineers and researchers to train their models on multiple machines (CPUs, GPUs, TPUs). Modern machine learning frameworks make it easy to do distributed training. The most common parallelization method with multiple workers is data parallelism: you split your data on multiple machines, train your model on all of them, and accumulate gradients. This gives rise to a couple of issues.

The most challenging problem is how to accurately and effectively accumulate gradients from different machines. As each machine produces its own gradient, if your model waits for all of them to finish a run -- this technique is called Synchronous stochastic gradient descent (SSGD) -- stragglers will cause the entire model to slow down.

However, if your model updates the weight using gradient from each machine separately -- this is called Asynchronous SGD (ASGD) -- it will cause gradient staleness because the gradients from one machine has caused the weights to change before the gradients from another machine has come in. How to mitigate gradient staleness is an active area of research.

Second, spreading your model on multiple machines can cause your batch size to be very big. If a machine processes a batch of size 128, then 128 machines processes a batch of size 16,384. If training an epoch on a machine takes 100k steps, training on 128 machines takes under 800 steps. An intuitive approach is to scale learning rate on multiple machines to account for so much more learning at each step, but we also can't make the learning rate too big as it will lead to unstable convergence.

Last but not least, with the same model setup, the master worker will use a lot more resources than other workers. To make the most use out of all machines, you need to figure out a way to balance out the workload among them. The easiest way, but not the most effective way, is to use a smaller batch size on the master worker and a larger batch size on other workers.

With data parallelism, each worker has its own copy of the model and does all the computation necessary for the model. Model parallelism is when different components of your model can be evaluated on different machines. For example, machine 0 handles the computation for the first two layers while machine 1 handles the next two layers, or some machines can handle the forward pass while several others handle the backward pass. In theory, nothing stops you from using both data parallelism and model parallelism. However, in practice, it can pose a massive engineering challenge.

A scaling approach that has gained increasing popularity is to reduce the precision during training. Instead of using a full 32 bits to represent a floating point number, you can use less bits for each number while maintaining a model's predictive power. The paper Mixed Precision Training by Paulius Micikevicius et al. at NVIDIA showed that by alternating between full floating point precision (32 bits) and half floating point precision (16 bits), we can reduce the memory footprint of a model by half, which allows us to double our batch size. Less precision also speeds up computation.

Most modern hardwares for deep learning take advantage of mixed and/or reduced precision training. Newer NVIDIA GPUs, such as Volta and Turing architecture, feature Tensor Cores, processing units that support mixed precision training. Compared to standard FP32 on P100, Tensor Cores provide up to 12x higher peak TFLOPS during training, and up to 6x during inferencing. Google TPUs also support training with Bfloat16 (16-bit Brain Floating Point Format), which the company dubbed as "the secret to high performance on Cloud TPUs."

Resources

- Training Neural Nets on Larger Batches: Practical Tips for 1-GPU, Multi-GPU & Distributed setups. Thomas Wolf. 2018.

- Demystifying Parallel and Distributed Deep Learning: An In-Depth Concurrency Analysis. Tal Ben-Nun and Torsten Hoefler. 2018.

- A Guide to Scaling Machine Learning Models in Production. Hamza Harkous, Hackernoon. 2017.

- Scaling SGD Batch Size to 32K for ImageNet Training. Yang You, Igor Gitman, and Boris Ginsburg. Berkeley EECS. 2018.

Serving

Before serving your trained models to users, you need to think of experiments you need to run to make sure that your models meet all the constraints outlined in the problem setup. You need to think of what feedback you'd like to get from your users, whether to allow users to suggest better predictions, and from user reactions, how to defer whether your model does a good job.

Training and serving aren't two isolated processes. Your model will continuously improve as you get more user feedback. Do you want to train your model online with each new data point? Do you need to personalize your model to each user? How often should you update your machine learning model?

Some changes to your model require more effort than others. If you want to add more training samples, you can continue training your existing model on the new samples. However, if you want to add a new label class to a neural classification model, you're likely need to retrain the entire system.

If it's a prediction model, you might want to measure your model's confidence with each prediction so that you can show only predictions that your model is confident about. You might also want to think about what to do in case of low confidence -- e.g. would you refer your user to a human specialist or collect more data from them?

You should also think about how to run inferencing: on the user device or on the server and the tradeoffs between them. Inferencing on the user phone consumes the phone's memory and battery, and makes it harder for you to collect user feedback. Inferencing on the cloud increases the product latency, requires you to set up a server to process all user requests, and might scare away privacy-conscious users.

And there's the question of interpretability. If your model predicts that someone shouldn't get a loan, that person deserves to know the reason why. You need to consider the performance/interpretability tradeoffs. Making a model more complex might increase its performance but make the results harder to interpret.

For complex models with many different components, it's especially important to conduct ablation studies -- removing each component while keeping the rest -- to determine the efficiency of each component. You might find components whose removals don't significantly reduce the model's performance but significantly reduce its complexity.

You also need to think about the potential biases and misuses of your model. Does it propagate any gender and racial biases from the data, and if so, how will you fix it? What happens if someone with malicious intent has access to your system?

On the engineering side, there are many challenges involved in deploying a machine learning model. However, most companies likely have their own deployment teams who know a lot about deployment and less about machine learning.

Note: The assumptions your model is making

The statistician George Box said in 1976 that "all models are wrong, but some are useful." The real world is intractably complex, and models can only approximate using assumptions. Every single model comes with its own assumptions. It's important to think about what assumptions your model makes and whether our data satisfies those assumptions.

Below are some of the common assumptions. It's not meant to be an exhaustive list, but just a demonstration.

- Prediction assumption: every model that aims to predict an output Y from an input X makes the assumption that it's possible to predict Y based on X.

- IID: Neural networks assumes that the data points are independent and identically distributed.

- Smoothness: Every supervised machine learning method assumes that there's a set of functions that can transform inputs into outputs such that similar inputs are transformed into similar outputs. If an input X produces an output Y, then an input close to X would produce an output proportionally close to Y.

- Tractability: Let X be the input and Z be the latent representation of X. Every generative model makes the assumption that it's tractable to compute the probability P(Z | X).

- Boundaries: A linear classifier assumes that decision boundaries are linear.

- Conditional independence: A Naive Bayes classifier assumes that the attribute values are independent of each other given the class. Normally distributed: many statistical methods assume that data is normally distributed.

Note: Tips on preparing

The list of steps above is long and intimidating. Think of a project you did in the past and try to answer the following questions.

- How did you collect the data? How did you process your data?

- How did you decide what models to use? What models did eventually try? What models did better? Why? Any surprise?

- How did you evaluate your models?

- If you did the project again, what would you do differently?

Resources

- Rules of Machine Learning: Best Practices for ML Engineering. Martin Zinkevich, 2017.

- How to build scalable Machine Learning systems - Part II: Architecting a Machine Learning Pipeline. Semi Koen, Towards Data Science, 2017.

- A Brief History of Machine Learning Models Explainability. Zelros AI, 2018.

- The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation. Miles Brundage et al., 2018.

- Fairness in Machine Learning Engineering crash course. Google.