Introduction

This part contains 27 open-ended questions that test your ability to put together what you've learned to design systems to solve practical problems. Interviewers give you a problem, possibly related to their products, and ask you to design a machine learning system to solve it. This type of question has become so popular that it's almost guaranteed that you'll be asked at least one during your interview process. In an hour-long interview, you might have time to go over only one or two questions.

These questions don't have single correct answers, though there are answers that are considered correct. There are many ways to solve a problem, and there are many follow-up questions the interviewer can ask to evaluate the candidate's knowledge, implementation ability, and critical thinking skills. Interviewers generally agree that even if you can't get to a working solution, as long as you communicate your thinking process to show that you understand different constraints, trade-offs, and concerns of your system, it's good enough.

These are the kind of questions candidates often both love and hate. Candidates love these questions because they are fun, practical, flexible, and require the least amount of memoization. Candidates hate these questions for several reasons.

First, they lack evaluation guidelines. It's frustrating for candidates when the interviewer asks an open-ended question but expects only one right answer -- the answer that the interviewer is familiar with. It's hard to come up with a perfect solution on the spot and candidates might need help overcoming obstacles. However, many interviewers are quick to dismiss candidates' half-formed solutions because they don't see where the solutions are headed.

Second, these questions are ambiguous. There's no typical structure for these interviews. Each interview starts with a purposefully vague task: design X. It's your job as the candidate to ask for clarification and narrow down the problem. You drive the interview and choose what to focus on. What you choose to focus on speaks volumes about your interest, your experience, and your understanding of the problem.

Many candidates don't even know what a good answer looks like. It's not taught in school. If you've never deployed a machine learning system to users, you might not even know what you need to worry about when designing a system.

When I asked on Twitter what interviewers look for with this type of question, I got varying answers. Dmitry Kislyuk, an engineering manager for Computer Vision at Pinterest, is more interested in the non-modeling parts:

"Most candidates know the model classes (linear, decision trees, LSTM, convolutional neural networks) and memorize the relevant information, so for me the interesting bits in machine learning systems interviews are data cleaning, data preparation, logging, evaluation metrics, scalable inference, feature stores (recommenders/rankers)."

Ravi Ganti, a data scientist at WalmartLabs, looks for the ability to divide and conquer the problem:

"When I ask such questions, what I am looking for is the following. 1. Can the candidate break down the open ended problem into simple components (building blocks) 2. Can the candidate identify which blocks require machine learning and which do not."

Similarly, Illia Polosukhin, a co-founder of the blockchain startup NEAR Protocol and who was previously at Google and MemSQL, looks for the fundamental problem-solving skills:

"I think this [the machine learning systems design] is the most important question. Can a person define the problem, identify relevant metrics, ideate on data sources and possible important features, understands deeply what machine learning can do. Machine learning methods change every year, solving problems stays the same."

This book doesn't attempt to give perfect answers -- they don't exist. Instead, it aims to provide a framework for approaching those questions.

Research vs production

To approach these questions, let's first examine the fundamental differences between machine learning in an academic setting and machine learning in production.

In academic settings, people care more about training whereas in production, people care more about serving. Candidates who have only learned about machine learning but haven't deployed a system in the real world often make the mistake of focusing entirely on training: getting the model to do well on some benchmark task without thinking of how it would be used.

Performance requirements

In machine learning research, there's an obsession with achieving state-of-the-art (SOTA) results on benchmarking tasks. To edge out a small increase in performance, researchers often resort to techniques that make models too complex to be useful.

A technique often used by the winners of machine learning competitions, including the famed $1M Netflix Prize and many Kaggle competitions, is ensembling: combining "multiple learning algorithms to obtain better predictive performance than could be obtained from any of the constituent learning algorithms alone." While it can give you a few percentage point increase in performance, ensembling makes your system more complex, requires much more time to develop and train, and costs more.

A few percentage points might be a big deal on a leaderboard, but might not even be noticeable for users. From a user's point of view, an app with a 95% accuracy is not that different from an app with a 96% accuracy.

Note

There have been many arguments that leaderboard-styled competitions, especially Kaggle, aren't machine learning. An obvious argument is that Kaggle already does a lot of the steps needed for machine learning for you (Machine learning isn't Kaggle competitions, Julia Evans).

A less obvious, but fascinating, argument is that due to the multiple hypothesis testing scenario that happens when you have multiple teams testing on the same hold-out test set, a model can do better than the rest just by chance (AI competitions don't produce useful models, Luke Oakden-Rayner, 2019).

Compute requirements

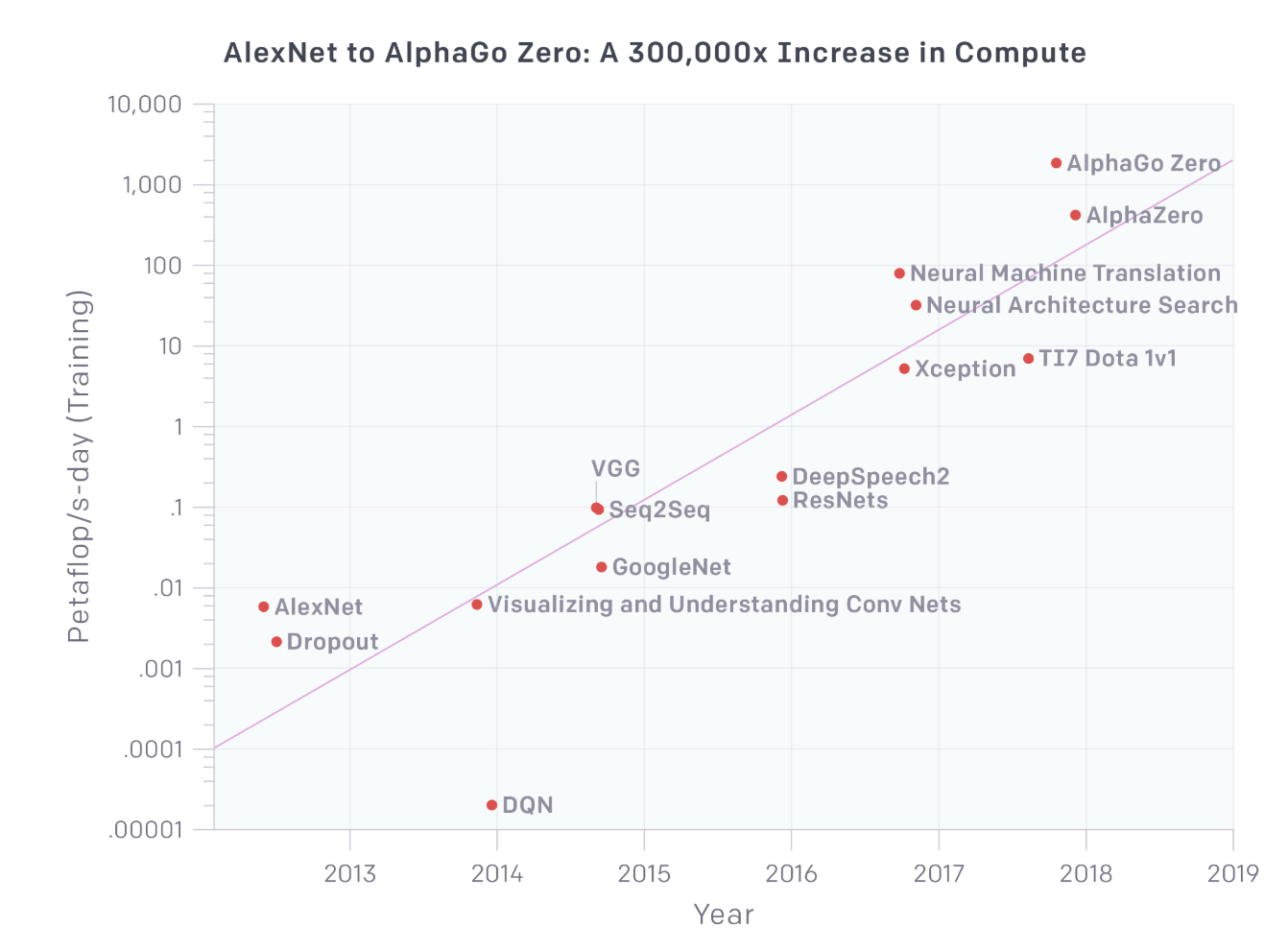

In the last decade, machine learning systems have become exponentially larger, requiring exponentially more compute power and exponentially more data to train. According to OpenAI, "the amount of compute used in the largest AI training runs has doubled every 3.5 months."

From AlexNet in 2012 to AlphaGo Zero in 2018, the compute power required increased 300,000 times. The architectural search that resulted in AmoebaNets by the Google AutoML team required 450 K40 GPUs for 7 days (Regularized Evolution for Image Classifier Architecture Search, Real et al., 2018). If done on one GPU, it'd have taken 9 years.

These massive models make ideal headlines, not ideal products. They are too expensive to train, too big to fit onto consumer devices, and too slow to be useful to users. When I talk to companies that want to use machine learning in production, many tell me that they want to do what leading research labs are doing, and I have to explain to them that they don't.

There's undeniably a lot of value in fundamental research. These big models might eventually be useful as the community figures out a way to make them smaller and faster, or can be used as pretrained models on top of which consumer products are developed. However, the goals of research are very different from the goals of production. When asked by engineers to develop systems to be used in production, you need to keep the production goals in mind.